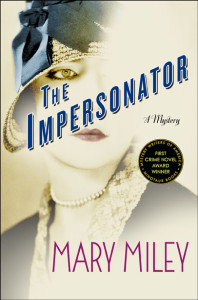

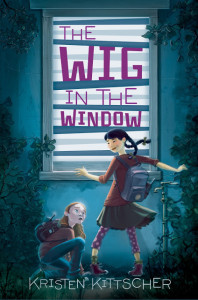

This month I read two awesome mysteries, Mary Miley’s The Impersonator, and Kristen Kittscher’s The Wig in the Window, and found myself in awe of both authors’ mastery of plot. I imagine mysteries to be a tough genre to write, but what do I know? So I asked Mary and Kristen how they went about plotting their stories.

The Impersonator is set during Prohibition (the Roaring Twenties) and geared toward adult readers, and The Wig in the Window is contemporary and written for young readers. As each plot unfolded, I noticed similarities in the structure of these novels, so I just had to know…

The Impersonator is set during Prohibition (the Roaring Twenties) and geared toward adult readers, and The Wig in the Window is contemporary and written for young readers. As each plot unfolded, I noticed similarities in the structure of these novels, so I just had to know…

A.B. Westrick: Did you outline the book before you began writing? How necessary is an outline when writing a mystery?

Mary Miley: I don’t outline in the high school sense (with Roman numerals and numbers and capital letters), but I am highly organized and I list my chapters or events in order, then decide when and how to work in the subplots before I start writing. As I go along, I make changes, of course, but I’m guided toward an end.

For mysteries, plot rules. Of course, characters are critical too, but the plot is what mystery readers are buying, and it needs to be intricate or surprising or challenging and complicated to succeed. A mystery writer, I think, needs to know the ending or the critical unexpected element before he/she even knows the beginning. For example, in the fourth of my Roaring Twenties series, which I am writing now, I knew the “trick” before I knew anything else—I knew the unusual way the murderer was going to kill his victim and how Jessie would know—and the police wouldn’t—who did it. I had nothing else for plot, just that. I am now in the process of constructing a plot around that critical element.

Kristen Kittscher: I didn’t outline The Wig in the Window up front but instead charged ahead blindly. I made a mess of things, took ages, then wrote an outline after the fact that helped me shape the story. I’ve taken the opposite approach with the sequel because I do think that outlining saves a great deal of headache (and heartache?), even if the story ends up deviating from the original outline. The ripple effect when you try to revise a mystery is extreme; with so many set-ups and pay-offs, it’s easy to get yourself in a tangle! Without some careful advance planning, you can end up with some elements that are almost impossible to change without rewriting the whole book.

Kristen Kittscher: I didn’t outline The Wig in the Window up front but instead charged ahead blindly. I made a mess of things, took ages, then wrote an outline after the fact that helped me shape the story. I’ve taken the opposite approach with the sequel because I do think that outlining saves a great deal of headache (and heartache?), even if the story ends up deviating from the original outline. The ripple effect when you try to revise a mystery is extreme; with so many set-ups and pay-offs, it’s easy to get yourself in a tangle! Without some careful advance planning, you can end up with some elements that are almost impossible to change without rewriting the whole book.

ABW: Okay, so plot rules and outlines help. You’ve confirmed my assumptions! A similarity that I noticed in your plot structures was that in both, the protagonist reaches a low point (fairly close to the end) where she’s sure that her efforts have been for naught. To what extent do you consider this down-in-the-dumps moment to be integral to the plot of a mystery? Do you know of any mysteries that do not structure the plot this way?

KK: Interesting question. I can’t think of any that don’t! However, I’m having trouble thinking of any story that doesn’t have that low point feeling, even in less plot-driven books. Perhaps that low point is essential to show a character changing and growing?

MM: It’s always effective for the reader to think things are hopeless for the protagonist. Make his life impossible, then let him figure out the final solution. Most mysteries, from James Bond to Nancy Drew, follow this pattern. In The Impersonator, Jessie reaches a low point after she’s figured out that the murderer is tied to bootlegging, and it doesn’t do her any good for two reasons. One, she can’t go to the police because during Prohibition, the cops were in cahoots with the crooks. Two, in her case, it’s a standoff—the murderer knows she isn’t the heiress because he killed the heiress. But he can’t turn her in for impersonating the heiress or he’ll hang for murder; she can’t turn him in or she’ll go to prison for fraud. So things get worse for Jessie. For me, that stand-off is the critical part of the book. The Impersonator isn’t a typical who-done-it, but rather a we-know-who-did-it-but-that-doesn’t-solve-the-problem book.

ABW: You’re reminding me why I wanted to feature these two books in the same blog post. The Wig in the Window would also fit the description, “we-think-we-know-who-did-it-but-that-doesn’t-solve-the-problem”! Now, let me ask about characters. In both of your books, a highly curious character sets out in search of evidence to explain something odd that she’s observed. This characteristic—curiosity—strikes me as the fundamental trait for the protagonist in a mystery. Do you agree? Disagree? In your writing process, which came first—the character(s) or the plot?

KK: I absolutely agree. Though I never set out intentionally to create curious characters, their relentless drive to discover more truths is what keeps the mystery’s pages turning. The characters came first for me. My first draft was an episodic collection of hijinks between two friends. I didn’t even understand I was writing a mystery, believe it or not. I thought that because I could write passable dialogue and some nice sentences, I could tell a story. I was very mistaken! Eventually, with a lot of help and feedback, I learned some story structure basics and carved out a plot.

MM: You may be right about curiosity, Anne, but I never thought of Jessie, my protagonist, as especially driven by curiosity. A lifetime spent on the vaudeville stage made her highly alert to nuance and expert at reading other people (the audience, the other performers on stage) because that was critical to her success. And success meant eating. The 1920s was an era when there was nothing even close to welfare, government assistance, or food stamps—you worked or you starved. At her lowest point, Jessie was completely without stage prospects and realized her only other option was prostitution. So she joined up with a swindler and become part of a scam to impersonate a missing heiress. Her sensitivity to people (she’s almost psychic) and her ability to get inside the heads of others gave her an edge in solving crimes. She noticed things that the police didn’t. More than curious, I thought of her as tenacious.

ABW: Good point, Mary. The characters in The Wig in the Window are tenacious, too. And both books are real page-turners. While writing, how conscious were you of the need to raise the stakes? How much of the novel’s tension was present in the first draft, and how much was added during the revision process? (How different is the final, published version from the manuscript that your editor first saw and on which you got your initial contract?)

KK: Thank you for calling it a page-turner! The final, published version is not drastically different from the manuscript my editor first saw. However, my very first draft and the one I ultimately submitted to my editor are barely recognizable! The Wig in the Window is my debut novel, and while writing, I was learning how to tell a story, so I was very conscious of the need to raise the stakes, create tension, and try to eliminate excess. It’s still a little bit more meandering and complicated than I would’ve liked, but there were limits to what I could do in revisions without pulling it all apart entirely. I’m still happy with it, of course—but that’s why I’m now an outlining evangelist!

MM: I never track the number of revisions I’ve made; it would be impossible, there are so many. For The Impersonator, at least 50. Maybe some writers can say that their first draft is great, but I can’t say that. I re-write and re-write and re-write before I even submit to my critique groups, and then I re-write some more after their input. I learn by revising. By the time my St. Martin’s editor saw (and loved) the manuscript for The Impersonator, there wasn’t much she wanted changed, and I accomplished her requested revisions in a couple days.

ABW: It’s helpful to hear how much revision happened before you showed your manuscripts to your editors.

MM: Absolutely. Revision is something all writers must do, and when I hear some complain about it, I cringe. When a critique group or an agent or editor says changes are needed, it’s because they want the book to be better. I once knew an agent who told me she had a client whose manuscript she managed to sell for a decent amount, and when that publisher requested certain changes in the manuscript, the author turned huffy and refused to make them. He thought his work was perfect as it was. The publisher, of course, backed out of the agreement and the agent dropped the client, and I can almost guarantee that he never sold his work anywhere with that attitude. Publishers and agents are on the writer’s side! In almost every case, their changes will improve the book.

ABW: Are both of you big readers of mysteries? What authors and/or books would you recommend for writers who want to pen a mystery?

KK: I’m a big reader of mysteries! I’m embarrassed to say that I never noticed what a mystery fan I was until after I wrote a mystery myself, but I do read voraciously in the genre. I’m a big fan of Kate Atkinson (Case Histories) and Tana French (In the Woods), as well as Scottish crime novelist Denise Mina. I like mysteries with richly developed characters—and I’m willing to sacrifice pacing to get them!

Kids’ mysteries I love include the Kiki Strike series by Kirsten Miller, about butt-kicking delinquent Girl Scout/detectives fighting crime in the underground tunnels of New York City, as well as the classics The Westing Game by Ellen Raskin and From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler by E. L. Konigsburg.

There are a lot of great resources for mystery writers: How to Write a Damn Good Mystery by James Frey has a silly title but great tips. Now Write! Mysteries, edited by Sherry Ellis and Laurie Lamson, has some outstanding exercises.

MM: I’ve loved mysteries since I discovered Nancy Drew at age eight. Back in the 1950s those books cost $2 each. I’d get one for my birthday and one for Christmas—the libraries didn’t carry them because they were “trash”—and I’d finish them in a couple hours. I pined for more, but there was no place to get them. So the best day of my young life was when an older neighbor girl went off to college and cleaned out her room, sending a couple dozen Nancy Drews across the street to my house. It’s a wonder I didn’t die of happiness. I still have them on the top shelf.

I graduated from Nancy Drew to James Bond (not the movies—the books), Agatha Christie, Josephine Tey, Sherlock Holmes, Dasheill Hammett, Laurie King, and Mary Roberts Rinehart. By and large, I prefer historical mysteries to contemporary (no surprise, as I am a historian) and like the more traditional mystery formula, not insipid “cozies” or extremely violent, bloody horrors. And as a mother, I simply cannot read any book about the killing of a child. I just can’t do it.

ABW: Any last words of advice for aspiring mystery-writers?

MM: Nope. Just good luck!!

KK: Having advice to give implies I know what I’m doing! I don’t have specific mystery advice, but I will offer some cheerleading: do not waste time worrying about whether you have talent or whether your writing is going somewhere. It will soon enough!

ABW: Thank you, Kristen and Mary! Your answers here have made me marvel at the many ways books affect us as readers. And let me just add that I hope the emphasis on revision doesn’t scare away any aspiring writers. Yes, revision is tough, but the pay-off (publication) is very sweet, indeed!