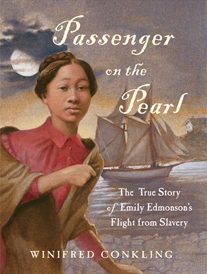

I met Winifred Conkling in 2009 when we were students in the MFA program at Vermont College of Fine Arts, and today I’m thrilled to feature her reflections on the craft of writing. Winifred is the award-winning author of numerous books and articles for adults and children, and her newest book, Passenger on the Pearl: The True Story of Emily Edmonson’s Flight from Slavery, comes out today from Algonquin Young Readers.

I met Winifred Conkling in 2009 when we were students in the MFA program at Vermont College of Fine Arts, and today I’m thrilled to feature her reflections on the craft of writing. Winifred is the award-winning author of numerous books and articles for adults and children, and her newest book, Passenger on the Pearl: The True Story of Emily Edmonson’s Flight from Slavery, comes out today from Algonquin Young Readers.

A.B. Westrick: Winifred, welcome!

Winifred Conkling: Thank you for inviting me, Anne.

ABW: Passenger on the Pearl is a heart-wrenching story that hooked me on page one. I can tell from the sidebars and source notes that you researched the life of Emily Edmonson and her contemporaries extensively. So my first question is how you distilled down what must have been a mountain of primary sources, and decided to begin the story where you did (with Emily’s mother’s fears about bringing children into the world)?

WC: I always struggle with where to start a story. You’re right, I started the process by reading piles of source material. I finally decided that the most natural way to frame the story was to focus on Emily’s birth into slavery and to end with her marriage and the promise that her children would be born free. In my background reading, I was devastated by the quote from Emily’s mother, Amelia, who had fallen in love but refused to marry, saying: “I loved Paul very much, but I thought it wasn’t right to bring children into the world to be slaves.” I am the mother of three, and I can’t imagine what it would feel like to know that my children would be destined to face the horrors of slavery. I know that young readers are familiar with the idea of slavery, but I wanted to make the suffering personal.

ABW: Well, you certainly did make it personal. Her suffering drew me in—it’s an excellent opening. Now let me ask some more about those primary sources, and about research in general. Research can be mesmerizing, and at the same time overwhelming. Do you have any advice to help writers recognize which sorts of historical nuggets make for great stories, and which to leave behind? In so many words, I guess I’m asking: why this story? Why Emily Edmondson? What was it about Emily that made you decide to tell her story rather than, say, the story of one of her brothers? Or the captain’s story?

WC: My first draft of Passenger framed the story around Emily and her sister Mary—the Edmonson sisters—who remained together throughout much of their journey. The problem with this approach is that Mary died as a young woman and I wanted the narrative to continue to Emily’s work as a teacher in Washington, D.C., as well as her later marriage. By focusing on a single character, Emily, I was able to more naturally complete the story and end with the birth of the next generation.

We struggled with Emily vs. Emily-and-Mary when designing the cover art. The front cover of the book shows Emily in the moonlight with the Pearl in the background. The art wraps around to the back where we see Mary and others who were also making their way to the ship. The intent was to emphasize that this is Emily’s story, but she was not alone.

Also, the choice to feature Emily was based on the primary sources available. Because of the family’s association with Harriet Beecher Stowe, the lives of the Edmonsons are well documented; Stowe had much to say about them in A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Also, the choice to feature Emily was based on the primary sources available. Because of the family’s association with Harriet Beecher Stowe, the lives of the Edmonsons are well documented; Stowe had much to say about them in A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

I’m glad you asked about the captain’s story. I loved his contributions, and we are fortunate that we have his autobiography available. (It was released by Project Gutenberg, e-book #10401-8.) His story is fascinating in its own right, but I had to resist the temptation to tell too much because this project was Emily’s story. I tried to share the relevant highlights and to let readers know what happened to him; he spent four years in prison as a result of his efforts to help seventy-seven enslaved people find freedom.

ABW: Through the first half of Passenger, I felt genuinely worried for Emily, and turned pages to find out what happened to her. I was totally caught up in her plight, and to be honest, I found the sidebars distracting. But somewhere along the line, a shift happened, and by the time I was well into the second half, I was lingering on each sidebar. So let’s talk about those sidebars! What went through your mind in crafting them? Were they part of your idea for this book from the start?

WC: I love sidebars. There are so many interesting bits of history and things to explore and explain that would slow down the plot but remain important for the reader to know. The main narrative tells the story—what happened to Emily—while the sidebars give the reader the background that deepens their understanding of context and history. Some readers will no doubt blow right past the sidebars to follow the story, and that’s okay. Others will stop and read them in order, which does slow the narrative flow, but helps to answer questions the reader may have along the way.

WC: I love sidebars. There are so many interesting bits of history and things to explore and explain that would slow down the plot but remain important for the reader to know. The main narrative tells the story—what happened to Emily—while the sidebars give the reader the background that deepens their understanding of context and history. Some readers will no doubt blow right past the sidebars to follow the story, and that’s okay. Others will stop and read them in order, which does slow the narrative flow, but helps to answer questions the reader may have along the way.

It’s not the just sidebars: The photos also interrupt the text, but I love them! The photos convey information and they remind the reader that this is nonfiction—these are real people and this is part of our shared American history.

I know some readers find sidebars distracting, but I think they serve an important function in nonfiction text. I didn’t set out to write a book with lots of sidebars, but as I wrote, they seemed inevitable.

ABW: Yes, and I admit that once I knew Emily’s story, I went back through the book and read the sidebars that I’d blown past on the first read-through. You have a lot of interesting tidbits there.

Now a question about proposals because I hear nonfiction writers talk about them: Did Passenger begin with a book proposal, and if so, what did that proposal look like? How long was it? Were the sidebars part of the first draft that your editor saw?

WC: I did not write a book proposal for Passenger. I knew I wanted to write about Emily—or Emily and Mary—and then I went to work. The structure changed several times in the process of writing and rewriting. The first draft I sent the editor did have sidebars, and we added some and deleted others along the way.

ABW: Was Passenger on the Pearl always the title, and if not, what were other titles under consideration?

WC: My original title was Ransomed: Emily Edmonson’s Escape from Slavery, but my editor didn’t like the word “ransomed.” (I liked it because to me it conveyed the idea that money was paid for the freedom of someone who was unjustly held captive.) We also played around with the title Forever Free, but we dropped that one, too. Titling books is tricky business, and I trust that the editors and publishers (and their marketing teams) have a better handle on it than I do.

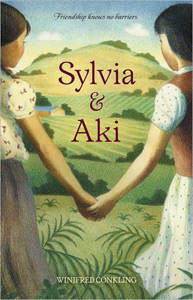

ABW: Your 2011 book Sylvia & Aki (Tricycle Press) won the Jane Addams Book Award for Older Readers. Congratulations! It was also historical, but on the advice of your editor at that time, you wrote it as “fictionalized history,” explaining that your editor “thought it would be more engaging to tell the story in a novelized format.” Now that you’ve written Passenger as nonfiction, would you reflect on the differences? I’m particularly interested in your reflections on the craft of writing. How is writing fiction different from writing nonfiction? Did you prefer the process of writing one more than the other?

ABW: Your 2011 book Sylvia & Aki (Tricycle Press) won the Jane Addams Book Award for Older Readers. Congratulations! It was also historical, but on the advice of your editor at that time, you wrote it as “fictionalized history,” explaining that your editor “thought it would be more engaging to tell the story in a novelized format.” Now that you’ve written Passenger as nonfiction, would you reflect on the differences? I’m particularly interested in your reflections on the craft of writing. How is writing fiction different from writing nonfiction? Did you prefer the process of writing one more than the other?

WC: Thank you — and congratulations to you, too [on Brotherhood receiving the Jane Addams honor]!

If I could do it over again, I would write Sylvia & Aki as nonfiction. The story is true; the only fictionalized parts involved the creation of dialogue. For that book, I interviewed Sylvia Mendez and Aki Munemitsu, the subjects of the book, and they both reviewed the text for accuracy before publication. The editor for that project believed that young readers would find it easier to relate to the story by presenting it as fiction with created dialogue.

Frankly, I struggle with this issue, and I think it’s an important question for authors to consider when writing stories that can be told as either nonfiction or fictionalized history (which isn’t the same thing as historical fiction, which I think of as a work of fiction set in the past). I don’t believe an author has the right to make up quotes. To me, quotation marks in nonfiction mean that the words—the exact words—can be traced back to a legitimate, contemporaneous source. That’s one of the main things that differentiates fiction and nonfiction; in nonfiction we don’t get to make up what was said or what happened.

When there are rich primary sources, I prefer writing nonfiction. It is an honor to be able to report and tell the story of history. That said, I also love historical fiction, especially when the historical period deepens and defines the character (like you did in Brotherhood). I don’t think one format is better than another; I think what is important is to be true to the format you have chosen as an author. Don’t leave the reader questioning whether a story is fiction or nonfiction.

ABW: Any final comments or words of wisdom for aspiring authors?

WC: Write the stories that haunt you. Whether you’re writing fiction or nonfiction, focus on the stories that captivate you. Those are the ones you’re supposed to tell.

ABW: Oooohhh, that’s just what I need to hear because my current work-in-progress is frustrating me, but I do feel called to write it—the story haunts me. So thank you for reminding me of that! And thank you so much for your insights today.

Great interview! I’m looking forward to reading Passenger on the Pearl and appreciate this discussion of the point of view, dialogue, and other challenges of writing narrative nonfiction vs. historical fiction.

Thanks, Lyn. I really enjoyed interviewing Winifred. The book is compelling! I hope your own writing is going great.

Thanks for this interview, Anne and Winifred, and congratulations, Winifred, on this latest book, it sounds fascinating! I loved reading your thoughts on historical fiction vs. fictionalized history vs. nonfiction. I am confident this newest book will be just as outstanding as your others! I am also fascinated by the process a writer goes through to arrive at their story, it’s so interesting to hear how you decided whose story to focus on. Anne, you asked just the right questions!

Meredith – I’m also fascinated by the process. It wasn’t until I was an adult that I appreciated how much of a process writing is. I just thought I was a lousy writer. But the more I came to understand the process — and especially my own process (which isn’t necessarily right or wrong, but is the way I do stuff) — I found that I could write, after all. (Revision is everything!)

And I do think Winifred’s words of wisdom are paramount: write what haunts you. It’s exhausting to visit the places that haunt us, but that’s where we’ll find compelling stories that are waiting to be told.