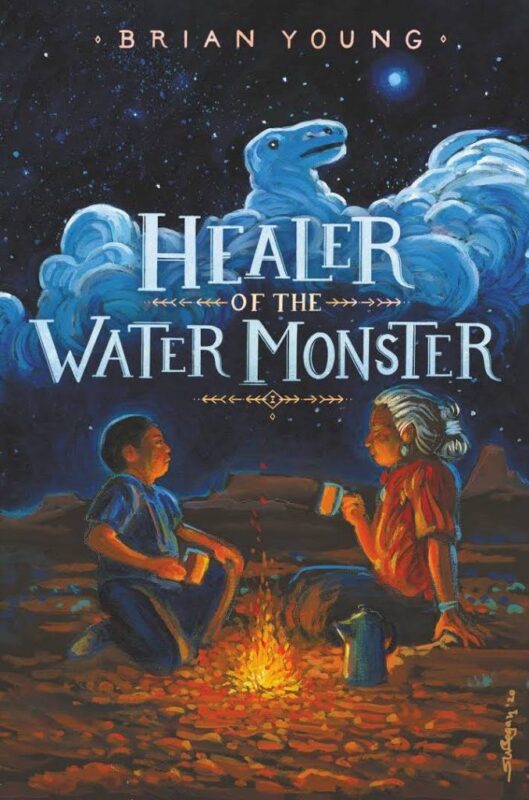

Congratulations to Brian Young on the release today of his debut middle grade novel, Healer of the Water Monster, out from Heartdrum, a new imprint at HarperCollins in partnership with #WeNeedDiverseBooks. I’m grateful to have gotten an Advance Reader Copy, and now that the book is out, I’m giving away one copy (hardcover)!

Jump to the end of this post to sign up for the giveaway, then come back to read what Brian has to say about writing this wonderful story. The deadline to enter the giveaway is Tuesday, May 18, 2021, at 11:59 PM.

Healer of the Water Monster is the story of an eleven year-old boy who spends a summer with his grandmother on the Navajo reservation where he encounters Holy Beings in need of help. It’s a story of courage, bravery and self-discovery, and it gives non-Native readers (like me) a glimpse into Navajo beliefs and practices as well as national policies that have injured the earth in general and the Navajo Nation specifically.

A. B. Westrick: Today, I’m thrilled that Brian is here on my blog to talk a bit about his writing process. Brian, welcome to my blog!

Brian Young: Good to be here!

ABW: I want to begin with the creation story in your prologue, but first, a confession: I’ve never liked the Judeo-Christian belief that God gave humans “dominion” over the earth (Genesis 1:26). I’ve much preferred an idea that I’ve understood to have been a Native American concept—the idea that we should honor Mother Earth and strive to live in unity with all.

BY: I think you might be referring to the Navajo philosophy of hozho—that we should strive to live in harmony/beauty with both Mother Earth and other peoples.

ABW: Yes, but I wasn’t ever taught that word. I didn’t know there was a name for it—that it’s called hozho.

BY: I’ll bet there’s a lot you weren’t taught about the Navajo nation!

ABW: Ha! I’ll bet you’re right!

BY: And can I add… you just said, “Native American,” but I’m always hesitant to group all native nations under the moniker Native American because there are over 574 federally recognized nations that have their own belief systems and history.

ABW: Oh my gosh, I’m so glad you corrected me. We’ve hardly begun and already I’ve misspoken. Thank you so much for being patient with my ignorance! I’m truly interested in learning more.

So let’s get back to the prologue… I have a question about the Navajo creation story (or “emergence story”) that you open with. The story is essential to the plot, and in your Author’s Note, you say that “[part] of being in an oral tradition culture means that, from family to family, there are variances on small details in the stories as well as restrictions of those stories.” How did your awareness of and respect for these variances influence you when you set out to write Healer of the Water Monster?

BY: Well first off, thank you so much for reading my Author’s Note! I realized that there were variations in the traditional stories when I was growing up on my reservation and playing with friends. We’d have these disagreements on how the stories went. The overall plot and story structure were the same but small details would be different. At certain ceremonies, there would be different grandmas and grandpas arguing, saying, “this is how you do this,” or “you shouldn’t do that,” or “you can’t talk about this during this time of the year,” or “yes, you can talk about this any time of the year.”

Part of what I do to keep my roots while living so far away from my homelands is that I read the traditional stories during winter. To research and write my book, I read four different books of the creation mythology and traditional stories, and I found a wide variety of details. In my initial drafts, I had these differences in the back of my mind.

I always knew that I needed to open with the story of the First Beings in the Third World because I had to situate readers in the mythology, and because not all Navajo would know which version of the story I grew up with. I added a small scene somewhere to mention this. I think it was the character Nali or Devin the Hataali who mentions this—that some people have been told that we currently are in the Fourth World and others have been told that we are in the Fifth World. That was my way to acknowledge the variances and validate multiple versions of the mythology. It was my way of saying, “I know of, see, and respect the variations of our creation story.”

ABW: This is fascinating. And I’m particularly impressed by your strong sense of respect for others and their understanding of the creation story. I’m really touched by that.

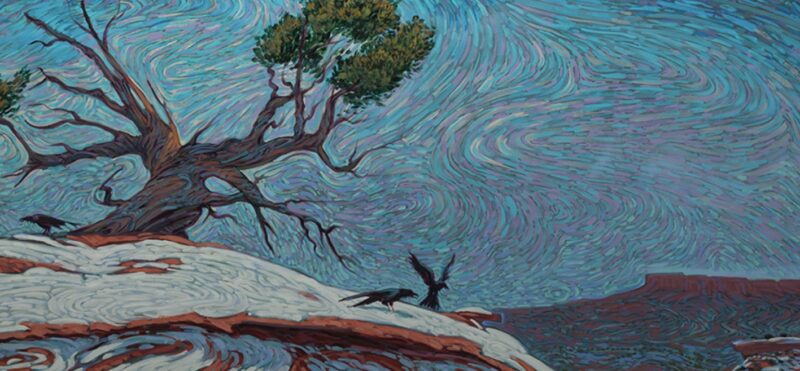

You know, I can even feel that sense of respect in your book’s cover art. When you told me Shonto Begay had done the cover, I found his artwork online and fell in love with many of the pieces. Like this one:

BY: It’s so very rare to have both an author and cover artist be Navajo on the same project!

ABW: Yeah, Heartdrum did an awesome job with your novel, and Shonto Begay’s work is mesmerizing. I’m grateful for his permission to include it here. When I first encountered the piece above on his website, SHONTOBEGAY.NET, it stretched across my whole computer screen. I could have looked at it for hours! (His site now features a different piece.)

Okay, now let’s get back to Healer of the Water Monster. Here’s a new question. In fiction, we talk about inviting readers to “suspend disbelief,” and to you I say, “Kudos for pulling it off!” I believed Nathan so completely that it wasn’t until I finished reading that I stepped back and wondered how much of the book reflected beliefs and how much was your imagination? Navajo readers will know, but I don’t! Could you give me one example of a faith element that you included in the story even though it was hard to write about? How did you deal with that difficulty?

BY: I think that the respectful interplay of belief systems and imaginations are what make #OwnVoices stories so precious and important, especially for the community that is being depicted. They’re authentic.

I think it is also important to note that culture doesn’t exist without people; people have their own history, thereby culture has its own history. With many indigenous nations, there is a history of fracture, white-washing, resistance, and survival. That’s where I think a lot of appropriators fail in their depictions; they focus on what they deem to be “pretty” and “romantic” without realizing that what they are stealing has survived that history. And it sure didn’t survive just so that it could be appropriated and stolen.

ABW: I appreciate you saying this because as a European-American, I confess that I’m just beginning to understand the many ways my majority/dominant culture has harmed minority cultures. I have a long way to go, and doing this interview with you is a huge leap forward! Thank you.

BY: Thanks for hearing me out.

Now, you asked about tough scenes. There was one I struggled with so much: the diagnosis scene. I’m still afraid that I showed too much! Some Navajos will say I did. If and when they voice their objections, I want people to listen to them and to ask what version of the emergence story they grew up with. If they are willing to share, of course. This isn’t only my culture; it’s theirs as well, and their version and restrictions of the traditional stories are just as important as mine. But yeah, the diagnosis scene is something I stressed out so much over. But I do feel confident and comfortable with how it plays out now.

ABW: What do you mean by “restrictions”?

BY: Restrictions are bits of info and stories and names I’m not allowed to share in any means outside of ceremonies or in-person context.

An example would be Coyote Stories. In the winter season after the last thunderstorm of fall and before the first thunderstorm of spring, we can tell and talk about coyote stories. But outside those time frames, we are forbidden from mentioning them. The reason is that some of the animals depicted in those stories hibernate during the winter. So out of respect, we only talk about coyote stories during the winter season.

Restrictions are rules that tells us what we can share or when we can share them, usually with a reasoning behind them.

ABW: Wow, this is all so new to me. And again, I love the sense of respect that comes through everything you’re saying.

BY: Yes. Respect runs deep. And as for restrictions, the way I’ve handled them is… think of it this way: with writing there are many ways to reference that something has happened. Like, say a character walks through a door. You don’t have to explain every single detail; you can just say that the door makes a sound as it closes shut. So you get the essence and the consequence of a door closing. And that’s what I did with the diagnosis scene.

I had Nathan look away at the stuff I knew I shouldn’t write down or show. In the story, he’s feeling nauseous, so he looks into the corner to endure the nausea. But for me, it’s a way to signify to those that participate in the culture that important events are occurring, but I respect the restriction and don’t show it. Thankfully, there is also context to Nathan’s nausea so it doesn’t read as obtuse and interruptive.

ABW: I wish you could see how big my eyes are, as I’m taking in what you’re saying. I’m realizing how much is going on between the lines. I’m just so impressed.

Now let me shift gears and ask about the many funny scenes, such as the conversation early-on when Nathan’s parents are avoiding each other and he’s stuck in the middle between them. Would your friends describe you as a funny guy? Is it easy for you to write funny scenes? Do they come naturally?

BY: I hope I’m funny! With Navajos, there’s a lot of teasing and joking around. I think that keeping in touch with the friends I grew up with has definitely helped me keep my Rez humor alive. When writing Healer, I didn’t think it was funny. I was too busy stressing out on what parts of the culture to share and not to share. I mean, that was all I was thinking about.

But I was fortunate to have critique readers tell me that certain scenes and moments were funny. My editor, too. And in revisions, I pushed the humor lever up. Like the spider scene. The first draft, I was focusing on Nathan’s fear of spiders and portraying the spiders as scary because I wanted it to be dramatic and suspenseful. But my initial reader was laughing when she read that scene. And I was like, wow, I failed miserably as a scary writer.

ABW: LOL, yes! I laughed out loud at the spider scene.

BY: Okay, good! And as I got feedback on scenes, when I felt that the story needed some levity, I would heighten it, or if it wasn’t an appropriate moment for humor, I would reduce it.

ABW: Well, you ended up with a good balance. You’re also good with sprinkling metaphors throughout your story, drawing readers in. For example, you wrote, “he heard the sigh of the midnight breeze” (pg. 18). I love that! How do you come up with phrases like that? Do you write by hand or at a computer? Do you have rituals that help you get your writing done, such as lighting candles or playing music or doing the work at a particular time each day?

BY: Oh gosh, I chug a bunch of black coffee. I bang my head against the wall. I scream at my computer. I question my existence and one sentence pops out. Then, my negative voice says that is the worst sentence and that I should quit writing.

That’s an exaggeration, but I mean, it’s not far off. I’ll go to YouTube for songs to listen to and inevitably end up watching the Top Ten Lists for Ways the World is Going to End Tomorrow. Then I’ll vacuum my room because the messiness is distracting me. Then there’s that load of laundry that needs to be done…

Eventually I write one sentence, then two sentences. And I tell that negative voice, “Thank you for your opinion, but now is not the time.” Later, when I go into revision mode, I say, “Thank you for being patient, I would like your opinions now.”

I work as a personal trainer on the side and I always tell my clients that progress is measured in inches not miles, seconds not hours. And book writing is a marathon, not a sprint. You have to be patient and just write. It’s also important to chug a bunch of coffee.

ABW: Ha! That’s great.

Now I’m curious about the glossary. One might say that a glossary imparts knowledge, and in your Author’s Note, you say that the idea that “knowledge should be provided easily and readily… is emblematic of a colonized mindset where the default is to take without considering the worth… With Navajo culture, knowledge is earned.”

Wow. These lines humbled me. They made me look up from the page and consider the many ways I’ve taken knowledge without stopping to offer thanks. So let me pause for a moment to say thank you for writing such a heartfelt Author’s Note… and also for including the glossary (which I loved and referenced a lot)!

My question is: did you know from the get-go that you’d include a glossary, or did that decision come later in your writing process? I guess I’m asking whether you sprinkled Navajo words and phrases throughout early drafts, or did you add them later? Could you share some of your thinking about how much Navajo language to include?

BY: From the get-go I was dead set on not having a glossary. I wanted the Navajo to exist on the page without translation because I wanted readers to experience not being fluent in your own language. That’s what it’s like for a lot of Navajo kids growing up on the Rez. Parents and grandparents will speak Navajo and the kid will be like, okay, I’m not going to be a part of that conversation. Navajo isn’t taught as a part of the core curriculum.

A lot of the people of my mom’s generation and my grandma’s generation are still recovering from the “Save the Indian, Save the man” policy era of education, when speaking their native tongue was punished. In reaction to that, those two generations didn’t view teaching English as important. So, my grandpa (who only spoke Navajo) and I didn’t have as deep a relationship as the one between me and my grandma who was able to speak English fluently.

But when my editor wanted a glossary, I ended up thinking, okay, I hope that Navajo kids out there will find value in the glossary. Maybe it will help teach them some Navajo, and will inspire them to learn the language, as I’ve been doing.

ABW: Right. There’s a lot to be said for learning the language.

Okay, finally, I see that you have a short story out in the anthology Ancestor Approved: Intertribal Stories for Kids, edited by Cynthia Leitich Smith, and I’d love to know: what are you working on now?

BY: I am currently brainstorming/researching several ideas. I feel my heart attaching to one storyline in particular but it’s way too early to talk about it. But one thing I can say is that when I sold Healer to Heartdrum, it was in a two-book contract. So I’m working on a follow-up to Healer of the Water Monster.

In this one, Guardians of the Water Monster, I’m taking Nathan into new challenges—the kind that a lot of Navajo and even indigenous children go through living in urban settings while maintaining their cultural identity and priorities. I was fortunate to be working on the follow-up while doing revisions to Healer, so I was able to sneak in several little Easter eggs to the second book. I hope they are subtle and don’t draw too much attention to themselves.

ABW: Oh, fun! I look forward to reading Guardians!

Thank you so much, Brian, for doing this interview and especially for being patient with me and explaining a lot. When I first contacted you, I had no idea how much I was about to learn. This has been a joy.

BY: Thanks for inviting me!

Readers who want to know more about Brian and his books can find him at Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and his website. If you visit, please let me know through the Rafflecopter below. (Be sure to visit Shonto Begay’s website, too!) Each entry earns you a chance to win a copy of Healer of the Water Monster.

The deadline to enter is Tuesday, May 18, 2021, at 11:59 PM. Multiple entries on multiple days are welcome. On May 19, I’ll ask the Rafflecopter to choose a random winner. Good luck!

a Rafflecopter giveaway