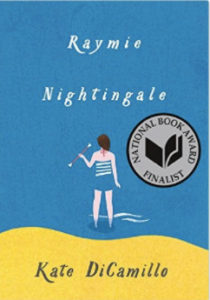

The other day while reading Raymie Nightengale by Kate DiCamillo, I hit a passage that from a craft of writing perspective was so good—so well written—it stopped me cold. I marveled at the technique, and knew in an instant I’d have to blog about it. So here we go. See what you notice in this excerpt from pages 5-6. We’re in the point of view of a young girl named Raymie who’s in a baton-twirling class with a teacher named Ida Nee. Standing next to Raymie is a girl who says…

“My name is Beverly Tapinski and my father is a cop, so I don’t think that you should mess with me.”

Raymie, for one, had no intention of messing with her.

“I’ve seen a lot of people faint,” said Beverly now. “That’s what happens when you’re the daughter of a cop. You see everything. You see it all.”

“Shut up, Tapinski,” said Ida Nee.

The sun was very high in the sky.

It hadn’t moved.

It seemed like someone had stuck it up there and then walked away and left it.

Oh, my gosh. Stop. Isn’t that great? (Or do you think I’m crazy?) Notice what DiCamillo does. Or what she does not do. She does not follow Ida Nee’s rebuke with Raymie’s opinion about Ida Nee. She does not tell us Raymie’s feelings. Instead, she describes what Raymie looks at.

As a reader, what do you feel?

How do you think Raymie feels?

The brilliance of this passage is the way DiCamillo trusts the reader to get it.

DiCamillo has used a creative writing technique with a rather obtuse name: the objective correlative. T. S. Eliot elaborated on this technique in a 1919 essay called “Hamlet and his Problems,” and when I was an MFA student at Vermont College of Fine Arts, author and faculty mentor Tim Wynne-Jones lectured about it. The essence of the technique is this: in order to communicate to readers what your character might be feeling, describe an object, situation, or set of circumstances that correlates with the character’s emotion. Don’t identify the emotion; let the reader infer it.

Eliot undoubtedly incorporated into his writing objective correlatives with more sophisticated language than what DiCamillo uses in Raymie Nightengale, but regardless of voice, style, or vocabulary, the effect is the same: the author stirs emotions in the reader without telling the reader what to feel. When done well, this technique is a highly effective tool in the show-don’t-tell toolbox.

If you want to read more about objective correlatives, I’d recommend this essay by a student at Carson-Newman University, and this explanation on the NeoEnglish website. See if you can revise passages in your current work-in-progress, removing words that name characters’ emotions and replacing them with objects or situations that communicate the mood or feeling in the scene. Write it well and readers will vicariously experience what the characters do. Good stuff.

Happy writing!

Thanks. Yep, good ole objective correlative. I seem to recall reading about it first in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s essay. And Eliot. You’re right. It can be very effective. This excerpt is perfect. Thanks for the links for further reading.

Good post, as usual!

I hate the name “objective correlative,” but once I wrapped my brain around its effectiveness, I got really excited about using it. Rarely do I think about objective correlatives when I’m writing a first draft, but on revision I try to enhance, tighten, and improve each scene.

Well done. I think people get tangled up in the term and think it must be something effete. And, mercifully, you didn’t quote Eliot’s explanation which would convince anyone that it was effete and beyond the understanding of all but the most precious of poets. Uh uh. It’s just what you say it is: looking at something and seeing it, and in describing it, transmitting a feeling. The best thing is not to try too hard — not attempt to make what is seen “meaningful” or, worse still, “symbolic.” If you’re looking through the character’s eyes, that should be enough.

Keeping it simple and not trying too hard. Yes! I’m so glad you lectured on the objective correlative when I was at VCFA. Great to hear from you.

I appreciate the clear explanation, which I should have used for my ninth grade writing students instead of whatever I did tell them and only about a third of them understood. Next time!

Thanks for this post! I remember the discussion at VCFA. I love seeing clear examples.

Yes, Lyn — next time!

Linda — I have to admit that when I was writing this post, there was a point when I paused, wondering if my example was too minimal. I double-checked my VCFA notes and listened to Tim’s lecture again, then read a bunch of articles about the objective correlative, and in the end decided DiCamillo’s writing was an excellent example. As Tim noted in his comment, sometimes writers try too hard. (Since “objective correlative” is such a mouthful, such a literary term, carrying the weight of more than a century of literary criticism, well, maybe the very suggestion of it tempts writers to try to go all out. But, ha! We don’t need to do that.)

Wow! This is a technique I’ve definitely seen, maybe not recognizing it as “objective correlative” before. I have a tendency to tell instead of show. Maybe this will help me show what’s happening, rather than telling. Thank you for this post!

You’re welcome! When I learned that there were techniques to good writing (that it wasn’t simply the case that some people had a gift for it and others not, but instead that writers knew a bunch of techniques they could teach to others), it made me very happy. 🙂

Thank you so much for this! Our first semester VCFA class has been grappling with all the hoopla and screams from the last graduate class around it. It seemed so intimidating and clearly it is not! Will have a listen to Tim’s lecture as well.

Hi Sue! Yes, the screams were funny, weren’t they? “Objective correlative… ahhhhh!” And I get that. The term is intimidating. It’s such a mouthful! But when we try to incorporate an OC into a scene, it needn’t be complicated. (It took me a while to unpack the term; even though I heard Tim lecture on it, I don’t think I really got it until after I’d graduated from VCFA.)