When James River Writers (JRW) invited me to interview some 2014 conference speakers, I looked over the impressive list of who’s coming and jumped at the chance to interview Kelly O’Connor McNees. I love the fact that she’d founded Word Bird Editorial Services. When she’s not writing her own fiction, she’s editing other people’s novels, so I figured she’d be perfect for my blog—as much in love with the process of writing as I am. And I was right!

When James River Writers (JRW) invited me to interview some 2014 conference speakers, I looked over the impressive list of who’s coming and jumped at the chance to interview Kelly O’Connor McNees. I love the fact that she’d founded Word Bird Editorial Services. When she’s not writing her own fiction, she’s editing other people’s novels, so I figured she’d be perfect for my blog—as much in love with the process of writing as I am. And I was right!

![]() Kelly will be speaking on panels during the JRW conference, October 18-19, 2014, in Richmond, VA, and on Friday, October 17, will lead a master class on “Point of View: Who’s Telling and Who’s Listening?” You can find more information on the JRW website.

Kelly will be speaking on panels during the JRW conference, October 18-19, 2014, in Richmond, VA, and on Friday, October 17, will lead a master class on “Point of View: Who’s Telling and Who’s Listening?” You can find more information on the JRW website.

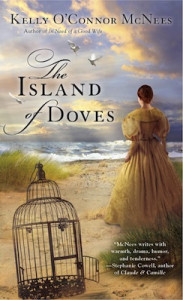

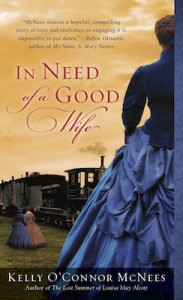

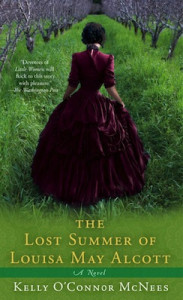

Kelly’s third novel, The Island of Doves, came out earlier this year from Berkley/Penguin. She’s also the author of The Lost Summer of Louisa May Alcott, and In Need of a Good Wife, which was a finalist for the WILLA Literary Award. I’m thrilled to share with you her wisdom on the writing process…

A.B. Westrick: Welcome, Kelly! I’ve just finished reading The Island of Doves, a beautiful novel set in Buffalo, Detroit, and the wilds of the Michigan Territory in the early 1800s, and I’d love to hear your comments on a few craft points.

Kelly McNees: Thank you for that very kind introduction! I am thrilled to be coming to Richmond for the conference and look forward to meeting lots of new friends and fellow writing geeks.

ABW: And they’re looking forward to meeting you! So let’s talk craft. I want to start at the beginning; usually I hate prologues, but yours drew me right in. You wrote it in scene, and I didn’t even notice that it was a prologue until five pages later when I hit the words, chapter one. At that point, the story had already hooked me. Very nice. Can you say a little about your decision to make that opening a prologue, rather than calling it a chapter?

ABW: And they’re looking forward to meeting you! So let’s talk craft. I want to start at the beginning; usually I hate prologues, but yours drew me right in. You wrote it in scene, and I didn’t even notice that it was a prologue until five pages later when I hit the words, chapter one. At that point, the story had already hooked me. Very nice. Can you say a little about your decision to make that opening a prologue, rather than calling it a chapter?

KM: I think of a prologue as a snapshot of an event that came before the main action of the story, which is why it works to set it apart that way rather than write it as a chapter. But I agree with you—typically I do not like prologues. They can feel tacked on and melodramatic. Sometimes they make a big promise that the novel can’t live up to. I added this one in a later draft, after I had tried and failed many times to communicate the events it describes (in much more elaborate ways) through flashback in other parts of the novel. Eventually I realized that we didn’t need to know the entire history of this family up front. We just needed to know about this one very important event, the death of the youngest sister, Josette, because it sets everything else into motion.

ABW: Good point. I can see how it sets up the action. Now tell me a bit about your approach to backstory. I was impressed by the way you wove backstory through the novel. For example, on page 77, I hit this line: “And of course, then there was the matter of her sisters.” Then you dropped the thread about sisters and returned readers to the scene, leaving us curious. Perfect! How conscious were you that you were doing this? Were the early drafts of the manuscript more backstory-laden than the final? How do you develop your characters’ backstory and decide which parts of it to feed the reader when?

KM: I am glad to hear that those transitions worked for you because I spent a lot of time thinking about them! This book had a lot of backstory and in earlier drafts felt very much weighed down by it all. A big challenge was that the bulk of the action that motivates one character, Magdelaine, happened decades before the story begins, and it’s difficult to create a sense of urgency around that. But even though so much time had passed, Magdelaine’s pain was very fresh, and I tried to evoke that by showing how much she was living in her mind, living in her memories, and that those things were just as real as what was happening in the present. Still, the reader must always feel anchored in the time of the story, and that’s why I worked to break that rumination up with interactions with characters in the present, and construct the story so that those present relationships helped her deal with the unresolved pain of the past.

Another thing I learned while writing this novel is that while it’s important to know your characters’ backstories in detail, not all of that information will make it into the novel. And that’s okay. You need to generate a lot of material, a lot of experiences from the character’s life, before you can select the emblematic experiences that will be most useful. One carefully chosen detail can communicate more about who a character is than five more generic flashbacks that attempt to get at the same thing.

ABW: These are great answers. Thank you! I know that dealing with backstory is always a tough issue for novelists. What about research? This book clearly required you to learn a lot about the Michigan Territory. When I got to your Author’s Note, I found your extensive list of sources. Could you say a bit about your process in researching? Got any tips for writers working on historical fiction?

KM: I learned a lot about research in writing this novel. I didn’t have much of an outline when I began, and because of that, I spent a lot of time letting the research shape the plot. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, but it is time-consuming. Basically, there is an infinite number of things about the history of Michigan, 19th-century greenhouses, nuns, steamboat travel, etc. that interest me, and at a certain point I had to cut myself off from learning about new things that would potentially take the plot in a yet another direction. The book was marooned for a long time while I tried to figure out what it was actually ABOUT. In fact, I put it aside for a couple years while I wrote In Need of a Good Wife, and then came back to it. When I did, I could see more clearly that everything has to start with the characters—who they are, what they want. Their desires have to drive the story.

So the first thing I would say about research is that the best way to use it, and not let it overwhelm you, is to envision the scope of your story (even if you don’t necessary have an outline) and then try to stick to researching within those boundaries. In historical fiction, there is a necessary tension between historical fact and story, but the story must always win. The information you gather about the past must be used in service of the story. Otherwise it will burden the reader. I spent six hours at the Harold Washington Library in Chicago reading about how native people built birch bark canoes, and there is maybe one sentence about that in the book. The details are interesting to me, but they are not, it turns out, very important to the story. Bad historical fiction happens when a writer wants to prove how much she knows, or “teach” the reader about events of the past. Snore!

So the first thing I would say about research is that the best way to use it, and not let it overwhelm you, is to envision the scope of your story (even if you don’t necessary have an outline) and then try to stick to researching within those boundaries. In historical fiction, there is a necessary tension between historical fact and story, but the story must always win. The information you gather about the past must be used in service of the story. Otherwise it will burden the reader. I spent six hours at the Harold Washington Library in Chicago reading about how native people built birch bark canoes, and there is maybe one sentence about that in the book. The details are interesting to me, but they are not, it turns out, very important to the story. Bad historical fiction happens when a writer wants to prove how much she knows, or “teach” the reader about events of the past. Snore!

ABW: I love your sentiment that “the story must always win.” Agreed! Also, I found your themes interesting. Your characters voiced some compelling views, and I wondered if you resonated with their ideas, personally (were they part of your thinking before you began the story), or did they emerge in the course of writing? Did you set out with a particular theme in mind? Some of the ideas that captivated me were: (1) victims of domestic violence may seek both freedom and safety, but in this world generally, safety is illusive; (2) more than fear, loneliness does people in; and (3) the earth accepts everything with complete indifference.

KM: You ask whether these are my views or whether they emerged as I wrote the story, and I think the answer is probably a little bit of both. I think I had these ideas, but I hadn’t examined them much until they came to the surface in this story. I have been fortunate not to experience firsthand the violence that Susannah did; my hope there was to put myself in her shoes and try to imagine what it would be like to be trapped in that house, in the wealth that so many people envied, and yet be miserable and afraid.

But, more broadly, the safety/freedom dichotomy has always been interesting to me. Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose, right? I think sometimes when we want to be free (not so much in Susannah’s case—literal freedom from violence—but in Magdelaine’s, who wants freedom from sadness), what we really want is to be safe and invulnerable, floating blissfully on some plane where we cannot be hurt. But the price for that safety is loneliness—total disengagement with others—because caring about someone makes you vulnerable. And I do think that loneliness is the greatest suffering of all.

Though this story does deal with some spiritual questions, I find much comfort, and I think Susannah and Magdelaine do, too, in nature’s indifference. The lake was there long before they were born, and it will be there long after they are gone.

ABW: Nice. I really enjoyed the depth in your novel, and your answer reminds me of its many layers.

Okay, now would you reflect for a moment on writing what you know? I happen to be Presbyterian, so I enjoyed phrases like the “clenched Calvinist jaw.” I felt both ownership and shame in scenes where Protestants slighted Roman Catholics (the historical authenticity rang true). Jerry Seinfeld might say you have to be a Jew to tell Jewish jokes; group-membership affords license to criticize or ridicule. My guess is that your background is Protestant, not Roman Catholic, because you portrayed the Protestants more critically than the Catholics. Care to comment? What are the challenges in writing as an insider versus as an outsider?

KM: In fact, I have much more experience with Catholicism! But it really was the historical facts of missionary work in the Northwest Territory that led me to depict the two groups as I did. The Catholics had been there since 1673, so about 150 years before the Protestants came. And while they influenced native communities in lots of ways, many of them negative, they did achieve a kind of coexistence. The Presbyterian approach was much more direct and interventionist, I guess you would say, and that was fueled by the ways their theology differed from Catholics’ (salvation through faith alone, rather than through good works—in other words, they could only save souls through conversion—and often that was forced upon native people).

So there was tension on that level. But also there was class tension masquerading as religious difference. In the UK, at least, where Edward’s family had come from, Protestants were wealthy landowners who controlled all political and economic power, and they saw Catholics as inferior in every way. So those tensions of course carried over into settlements in America, like Buffalo and Detroit and Mackinac, where Protestants continued to enjoy economic privilege, and Catholics occupied a working-class position and were beholden to them. I am oversimplifying a very complicated relationship, but those are a few of the issues that underlie their uneasiness with each other.

ABW: Interesting! I’d like to hear more, but we’ve gone on for a while already, so we’d better wrap it up here. I’d love to hear your reflections on working as a freelance editor. What are the most common mistakes that you see new/aspiring writers making? When clients have disagreed with your editorial comments, how have they handled those issues, and how have you responded?

ABW: Interesting! I’d like to hear more, but we’ve gone on for a while already, so we’d better wrap it up here. I’d love to hear your reflections on working as a freelance editor. What are the most common mistakes that you see new/aspiring writers making? When clients have disagreed with your editorial comments, how have they handled those issues, and how have you responded?

KM: I think many writers spend a lot of time researching how to find an agent or researching options for self-publishing, but maybe not as much time working to develop their craft. Learning how to identify your strengths and weaknesses as a writer, and then doing the hard work of developing your skills, can be a slow, difficult process, and there’s a temptation to rush through it. This is something all writers have to push against, and I certainly see it in the writers I work with.

I also urge clients to read as if their lives depend on it—and they do! (Well, their writing lives, anyway). Writers must read, read, read, and read some more.

As for giving feedback, I have lots of experience being on the receiving end of tough editorial comments, and I know how difficult it can be. I talk with my clients about how, to a certain extent, this kind of feedback is subjective, and as the author of the book, they of course must decide about which suggestions to take and which to disregard. And as much as possible I strive to make all feedback specific and actionable, and by that I mean that if I tell them something isn’t working, I have to be able to tell them why and how to fix the problem. But overall, things never get contentious because this isn’t about me, and it isn’t about being right. We are on the same team, both invested in making the book as strong as it can possibly be. And good writers can disagree about how to accomplish that. My role is to make suggestions and offer support as the author navigates the revision process.

As for giving feedback, I have lots of experience being on the receiving end of tough editorial comments, and I know how difficult it can be. I talk with my clients about how, to a certain extent, this kind of feedback is subjective, and as the author of the book, they of course must decide about which suggestions to take and which to disregard. And as much as possible I strive to make all feedback specific and actionable, and by that I mean that if I tell them something isn’t working, I have to be able to tell them why and how to fix the problem. But overall, things never get contentious because this isn’t about me, and it isn’t about being right. We are on the same team, both invested in making the book as strong as it can possibly be. And good writers can disagree about how to accomplish that. My role is to make suggestions and offer support as the author navigates the revision process.

ABW: Thank you so much for giving everyone at JRW a glimpse into your writing style and your work as an editor. We look forward to meeting you in Richmond later this month!

KM: I can’t wait! Thank you!