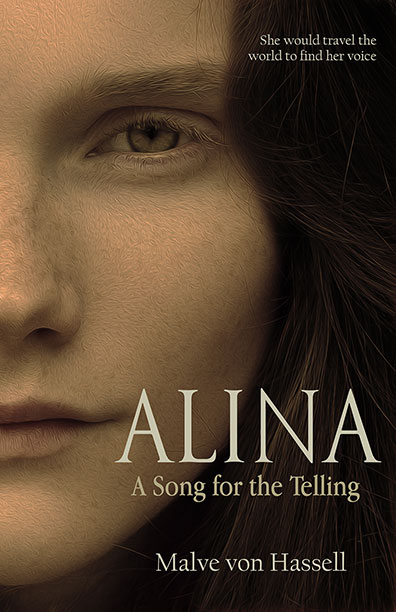

Calling all lovers of historical fiction! I’ve just read the newly released upper-middle grade novel Alina and with me today is author Malve von Hassell to tell us a bit about her writing process.

Set in 12th century Europe and the Middle East, Alina is the story of a fourteen year-old girl who travels from France to Jerusalem and encounters a few “real people” along the way, such as Stephen I, Count of Sancerre.

But first, if you know my blog, you know the drill. I’m doing a giveaway! Hop to the end of this post to sign up for the giveaway, then come back to read the interview. Deadline to enter: Wednesday, September 30, 2020, 11:59 PM.

A. B. Westrick: Malve, welcome to my blog!

Malve von Hassell: Thank you, Anne, for hosting me.

ABW: Let’s start with the time period, the 12th century—an era of kings and princesses, counts and troubadours, serfs, servants, slaves and The Crusades. What was it about this century that made you want to set the novel then?

MVH: As a child growing up in Europe, I read books about the Crusades and was mesmerized and puzzled by the willingness of people to embark on such long, arduous, and dangerous journeys in pursuit of a goal that I couldn’t comprehend. The notion of reclaiming the Holy Land and Crusades as military campaigns to gain political and territorial advantage got mixed up in my mind with the notion of Crusades as pilgrimages—both equally incomprehensible to me. I also read songs written by troubadours as part of our school work in Germany; however, it wasn’t until much later that I learned about the existence of the female troubadours, the trobairitz. Discovering them was eye opening.

ABW: I hadn’t heard of them, either, so it was great that you created a protagonist who wanted to become a trobairitz.

MVH: That was my start but meanwhile, purely by accident I came upon the central historical character and decided to build my story around him.

Stephen I, the first Count de Sancerre (1133–1190) is a fascinating figure. For instance, he chose to gives his serfs their freedom, a remarkable act in the 12th century. But that alone wasn’t what caught my attention. His story contains an intriguing blank spot. He accepted a proposal of marriage, by the standards of the times suitable at all levels. He settled his affairs and embarked on a long journey, bringing substantial gifts with him. Then, after a few months of contemplation, the groom returned home. Reminiscent of “the dog that didn’t bark” in a Sherlock Holmes mystery, the marriage didn’t take place. The historical record doesn’t expand on this. One can’t help but wonder what happened.

ABW: Right. In your novel he visits young Sibylla of Jerusalem (c. 1160-1190), then doesn’t marry her. It’s fun to speculate why.

While reading, I glanced at a map and tracked your fictional protagonist on her journey from Lyon (France) to Jerusalem via Venice (on the map below, I circled those three cities). It was a wonderful geography lesson! From the book I learned that Alina’s route was well-traveled, and I wondered how you went about finding information like that—ancient travel routes and such. Tell me a little about your research.

MVH: Research is like following along a convoluted trail with many side paths and dead ends. I enjoy it enormously, because you never know what you might find. The sources I use are too many to list here. Some are treasured books in my possession such as several old historical atlases; these helped me in figuring out exactly which routes Crusaders used in the 12th century. Meanwhile, the Internet is a wonderful resource, especially for armchair travelers. It also has provided a way to contact people all over the world with questions about certain details. I have found that one of the most gratifying experiences is the enormous generosity and kindness of experts, historians, and others with whom one might correspond in the quest for information.

ABW: You mention a number of historical sites (for example, the Bulgarian monastery with its unlocked door), and I figured you must have visited these places. Am I right? To what extent did you use first hand observations to supplement your research, and how much were descriptions purely from your imagination?

MVH: To my infinite regret, I have not yet been able to travel to the historical sites that figure in my story. Meanwhile, the little church in Bulgaria was inspired by ancient wooden churches in Ukraine that I was able to visit. Entering into those spaces is a profoundly moving experience regardless of what your particular belief system may be. I wanted to convey some of that. I hope that one day I might be able to travel and inspect for myself ancient Byzantine baths that have survived in the region.

Fortunately I could draw on a wealth of images and detailed descriptions of Byzantine, Greek, and Roman baths. For Alina, having grown up in a presumably drafty stone manor where bathing would involve sitting in a wooden tub in bathwater she might share with her sister, the baths outside of Venice and in Bulgaria must have been a sheer pleasure. Meanwhile, in my writing I tried to stay close to what we know of the reality of the time. Historical fiction has to bring a certain time and historical characters to life but refrain from changing them for the sake of a story.

ABW: You can’t change the history, but in fiction it’s fair to imagine how dialogue might have gone. I really liked a particular line that you put into Stephen’s mouth: “A journey to the Holy Land is a harsh school… Nobody who comes here will be quite the same, if and when they return” (page 112). I sensed in this line both the book’s theme and perhaps a glimpse into your own life and travels. While you were writing, were you conscious of this theme, or did it emerge organically and (perhaps) subconsciously?

MVH: This is an interesting question. I have moved repeatedly in my life. As a result of my father’s work as a diplomat, I was born in Italy. We lived in Belgium where I started school and then in Germany before moving to the U.S. I ended up making the U.S. my home. Whenever I return to Germany, I realize once again how profoundly my experiences here have changed me and would make it challenging for me to live once again in the country of my original nationality. So to answer your question, I have an affinity for people who embark on journeys and for individuals who miss home at the same time as they feel alienated from it.

ABW: Ahhh, missing home and at the same time feeling alienated from it. I imagine many have felt that way.

Now, in your bio, I see that in addition to earning a PhD in anthropology and writing The Falconer’s Apprentice (Namelos 2015), you’ve also published nonfiction. In terms of your writing process, do you find fiction or nonfiction easier to write? Or are they just different? Do you approach them the same way? Do you prefer one to the other?

MVH: There are no easy answers. I think that in some respects, writing fiction is immeasurably harder. You may have a fully developed, complex, and colorful internal image of a story and a set of emotions you want to convey, but succeeding at that is elusive. Both non-fiction writing and fiction involve a process of telling a story and conveying something that is true and real about an era or place in history or the lives of certain characters.

Academic works such as a study of community gardeners in New York City and works of fiction present a constructed reality in that one must choose what to leave out and what to include. This is difficult enough; a writer of fiction moreover has to turn this constructed reality into an exciting story. For historical fiction writers it becomes a balancing act of including history without drowning the reader in it.

I confess that I have not managed this balancing act successfully, too often forgetting the story over the history. Meanwhile, there is absolutely nothing that compares to the joy of coming up with a sentence in your work of fiction that seems completely right—at least in its first draft—or to walk through the woods and suddenly come up with a solution for solving your main character’s predicament.

ABW: Yes, agreed! Those moment of coming up with the right sentence or solution make it all worthwhile.

Finally, do you have any advice for aspiring authors who hope to tackle historical fiction?

MVH: The most important advice I can give is to find something that you feel strongly about. That is, find an incident, an era, or even a particular historical character to love or to hate. Find something that fascinates you so much that you feel compelled to incorporate it into your writing. That feeling alone can carry you through the long and often wearying times of putting it all together.

Make no mistake. Writing is hard work. But when you truly love a subject matter, the actual process of writing is more rewarding than I can express. Does one always succeed? Probably not. But you keep working, and you get better. It helps to have a steady day job that sustains you and gives you the peace of mind to write in your spare time. It’s worth it.

ABW: Helpful words. Thank you! What are you working on next?

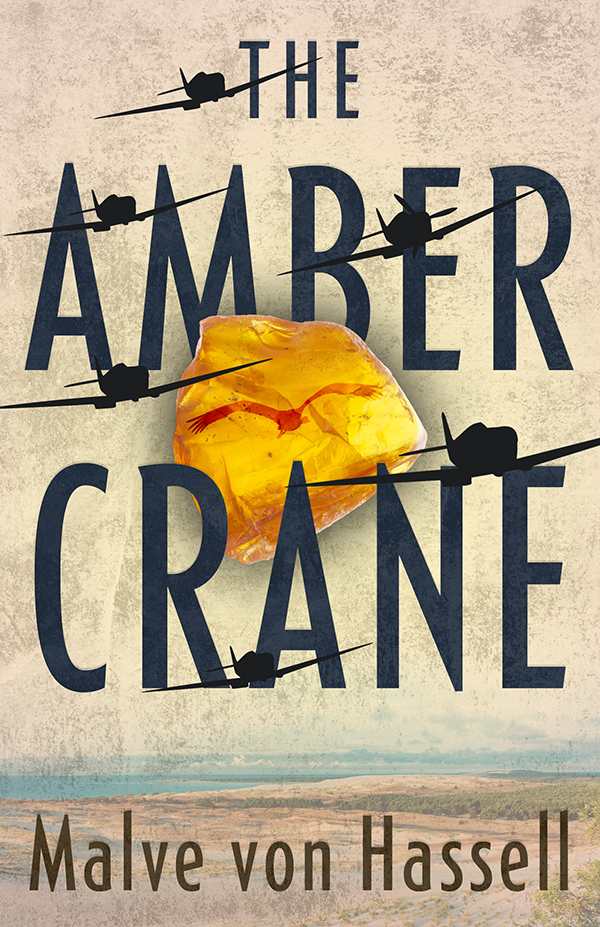

MVH: My upcoming release is set in a very different time from the 12th century; in fact, it is set in two time periods, the Thirty Years War and World War II. In the book, The Amber Crane (Odyssey Books, 2020), my protagonist, an apprentice in the amber guild, lives at the Baltic sea coast in a German town called Stolpmünde in the final years of the Thirty Years War. He finds a piece of amber on the beach. Even though he knows the severe penalties imposed on such an action, he keeps the amber, with potentially disastrous consequences for people close to him. Meanwhile, unaware of the amber piece’s magical powers, Peter finds himself drawn into a world three hundred years in the future where he gets embroiled in the troubles of a mysterious stranger.

ABW: Oooohhh, sounds compelling. Thank you so much, Malve, for taking the time to do this interview.

MVH: Thanks for inviting me! Your questions were wonderful. They made me think and allowed me to reflect once again about all the things I loved while working on this book.

ABW: Sweet to hear. I enjoy coming up with meaty questions!

Readers interested in more can find Malve von Hassell at her website , Facebook, Twitter, BookBub, and her publisher’s site, BHC Press. If you visit any of these sites, be sure to say so in the Rafflecopter below! Each entry gets you a chance to win a copy of Alina. Deadline to enter: Wednesday, September 30, 2020, 11:59 PM.

First of all, a wonderful photo of the book cover. This middle grade fiction interview was intriguing. I imagine Malve von Hassell’s work to weave two worlds, our own and the 12th century. How challenging. I’m writing a book set in the Middle Ages, my wizard characters probably need more grounding in their era. This interview has me thinking. Since all manuscripts are in process until they’re published, there’s time for more research. I’ll go back to my original notes, then more! Thanks.

Agreed. Awesome cover art!

And yes, Malve walked a fine line between our world and the 12th century. She made Alina feel relevant to today’s readers by showing how frustrated she felt with the restrictions placed on girls. In contrast, her brother experienced great freedom simply because he’d been born male.