Animal, mineral, vegetable? My family loves to play Twenty Questions. We always start with these three categories to narrow the field, but it never occurred to me to ask where the categories came from. Now I know!

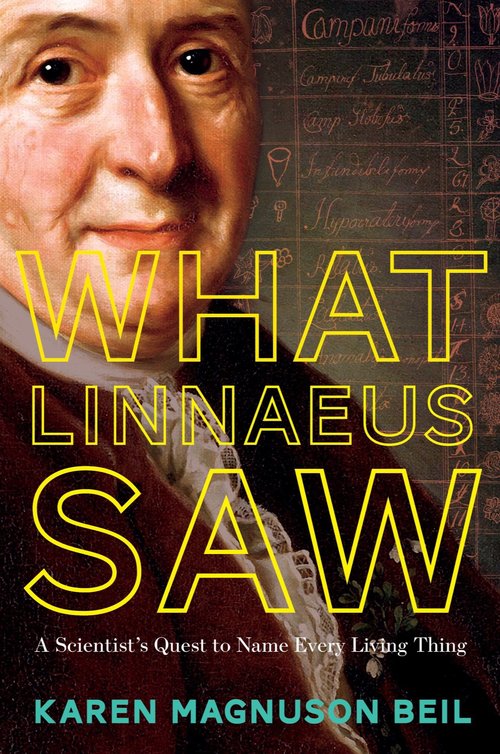

Karen Magnuson Beil‘s new biography, What Linnaeus Saw, is a fun and engaging look at Carl Linnaeus, the man who set out to name every living thing, building on Aristotle‘s study of the three kingdoms (animal, mineral and vegetable).

And Karen is here on my blog today! But before we get to the interview, hey—just in time for holiday gift-giving, I’m shipping one copy of What Linnaeus Saw to a lucky reader. Hop to the end of this post to enter the drawing (I’ll announce the winner on December 12), then come back to hear a bit about Karen and her writing process. The deadline to enter is Friday, December 11, 2020, at 11:59 PM.

A. B. Westrick: Karen, welcome to my blog. What a fun biography!

Karen Magnuson Beil: Thanks for the wonderful compliment and for inviting me to chat with you, Anne!

ABW: I’m so glad you were able to carve out time to do this interview.

KMB: Always thrilled to talk about craft with fellow writers and book people!

ABW: Awesome. Me, too. Now, let’s start with the opening of the book. I love the playful way you begin with a sort of riddle. Linnaeus has been given an animal he’s never before seen, and as he studies its ways and preferences, you don’t tell readers what it is. (Readers: it’s an animal you’ll recognize immediately, but Europeans in the 1700s wouldn’t have known it.) So, tell me, Karen, was this always your chapter one?

Multi-tasking in Chapter One

KMB: Far from it! I have a drawer full of starts! The first chapter is often the hardest to write because it has to accomplish so much—set the tone, point the book’s direction, give the reader a reason to keep on reading. In this case, it also has to orient the reader in another time and place, as well as introduce a little-known main character whose names for the world’s plants and animals are still used today. Tall order!

ABW: Yes, a very tall order. And you pulled it off. How did you come up with the idea of introducing Carl Linnaeus by way of this “mystery animal”?

KMB: Of all the terrific stories from his life, I felt this “mystery animal” story was the most relatable, one that would resonate with readers. I wanted the reader’s first encounter with Linnaeus to be exciting and memorable—the way his students described being with him on field trips. So, instead of starting in childhood, we first see him as a world-famous scientist and father of young children who’s in the middle of a science mystery. Adventure! Suspense! In medias res!

ABW: So fun!

KMB: The “mystery animal” story shows best who he was as a person because it captures both his serious study of nature and his intense emotional and sometimes playful connection with it. Children feel similar strong bonds with nature—thanks to their pets, outdoor experiences, their reading, even the nature shows they like to watch.

And thanks for not giving away the secret, Anne! Keeping the reveal hidden while dropping clues here and there is hard to do, but it’s half the fun. Ah, the agony of suspense! Fun fact: When the book’s designer initially laid out these pages, the image of the “animal in question” appeared several pages too early. Fortunately, my editor rejiggered the layout. No spoiler!

ABW: Good catch. While reading, I had an urge to peek ahead, hoping I’d find an illustration. Then I made myself wait. I wanted to guess it on my own. I finally did, but not until I was just a few paragraphs from the reveal. Well done!

KMB: Hey, bravo, you—resisting temptation! I’ll bet you can walk by a piece of chocolate, too.

ABW: Am I that easy to read? Hahaha. I love chocolate, but yes, I can walk by a piece. And that’s a story for another time! Back to your book…

In chapter two you present another mystery (why does pruning a pumpkin plant cause it to fail to produce fruit?) and you don’t solve it right away, either. This is a wonderful way to tap into a reader’s innate sense of inquisitiveness.

Science is Mystery

KMB: Science is Mystery. That’s what I find so exciting about it! Who doesn’t love a good mystery? I structured the book around this very idea.

I think creating structure is one of the most important steps in writing any book, nonfiction or fiction. Wherever I could, the chapters focused on an important problem—a mystery—that led Linnaeus to come up with a solution, a deeper understanding, or an ah-ha moment. This invites the reader into Linnaeus’s world. We’re right there on a quest with Carl struggling to solve big questions and learning as he learns.

Since young readers are curious, inquisitive and smart, I occasionally pose a probing question to inspire the reader to think through the problem and guess the outcome.

ABW: That’s great. Would you describe yourself as a particularly inquisitive person? Have you always been a lover of science and scientific discoveries?

KMB: Yes, to both! Asking questions is what I do, as a journalist and as a mother. In fact, before I begin research, I make a long list of questions, including those I would have had at my reader’s age. I’ve always been fascinated by how the natural world works and also by the names of things: people, places, plants and animals. When I was a child and my family went camping, I’d ask for the name of any new plant we spotted. (My favorites: pipsissewa, Indian pipes, lady slipper, and princess pine.) Today, my goal is to write books that I would’ve loved as a child.

ABW: Hahaha. Okay, so I had to look up pipsissewa. Love it!

New question: what was it about Linnaeus that made you want to write his biography?

KMB: The first spark came during a visit with relatives in Sweden. On a rainy October day, my forester-husband and I walked through Linnaeus’s garden in Uppsala. I was fascinated that the plants were organized not by color, shape or size, but by habitat—river, lake, marsh. It showed an understanding of the importance of ecosystems. I came to see his pioneering work was a bridge between old science and new, and between myth and reality. The intersection of ideas intrigues me.

Old Science vs. New

ABW: “Between old science and new” gets me to my next question. I really enjoyed how much I learned from the book. For example, now I know where the label homo sapiens originated, plus labels like mammals and primates, and I found it fascinating that Linnaeus, living a century before Darwin, got flack for grouping humans with apes and monkeys but didn’t imagine that humans could have evolved from apes. Evolutionary theory wasn’t yet a thing.

Clearly, Linnaeus’s work was something of a balancing act between new discoveries and long-held beliefs, and so here’s my question: it seems to me that writing his story would have required a balancing act on your part. How did you go about deciding what to keep in the book and what to leave out?

KMB: That’s such a great question! Deciding what stays and what goes is always a challenge, especially when it comes to balancing old and new science. While my primary mission was to tell the story of Linnaeus’s work, science has advanced in the past 250 years! So, I occasionally took a moment to update some of his science, as I did with the mystery animal and, later in the book, with a mystery plant. Since I never want to stray too far from my focus, I’ve come up with ways to keep myself in check.

Create a Fluid Structure for your Book;

Organize Your Ideas Visually

One is to create a good structure that’s fluid and subject to change. Since the science can be complicated, I add it slowly, building it layer by layer. I map out the flow of chapter details on colored notecards tacked to my office wall. (Don’t worry: it’s cork.) This helps me organize ideas visually. I need to be able to see the flow of information and how all the pieces fit together before I cut anything. The wall also allows me to move chapters around. Each chapter presumes knowledge from the previous chapters. As I move chapters, I can make sure that the reader’s knowledge base is growing bit by bit. If a story or fact doesn’t fit the flow, I cut it. Ruthless!

ABW: Now you’re talking about the old writing adage, “Kill your darlings.”

KMB: Exactly. But here’s my problem: I am utterly fascinated by too many subjects. What I love most about research is following tangents! Some writers call them “rabbit holes” and think they waste time. Maybe. But for me, a tangent is a playful experiment, a detour that can lead to new discoveries. By giving curiosity a little free rein, I’ve learned so many incredible things. The downside is there isn’t room for every intriguing fact I find. So, I’ve come up with some tricks to handle information that doesn’t quite fit but is just too good to leave out.

Tricks for Tangents

First, I tuck some into sidebars. For example, one sidebar discusses the fascinating story of Linnaeus’s friend Anders Celsius, who designed an early experimental thermometer.

Second, I salvage some as picture captions. For instance, my caption for a terrific poster advertising the zoo at Blue John’s tavern, which Linnaeus frequented in Amsterdam, includes this gem: “Lions were kept inside the inn in flimsy wooden enclosures; to see them cost extra.” (If you dared!)

ABW: Haha. Right. If you dared! Clearly, you did an enormous amount of research to get the details of Linnaeus’s life and studies straight. Could you share one highlight from all of your research?

The Joy of Research

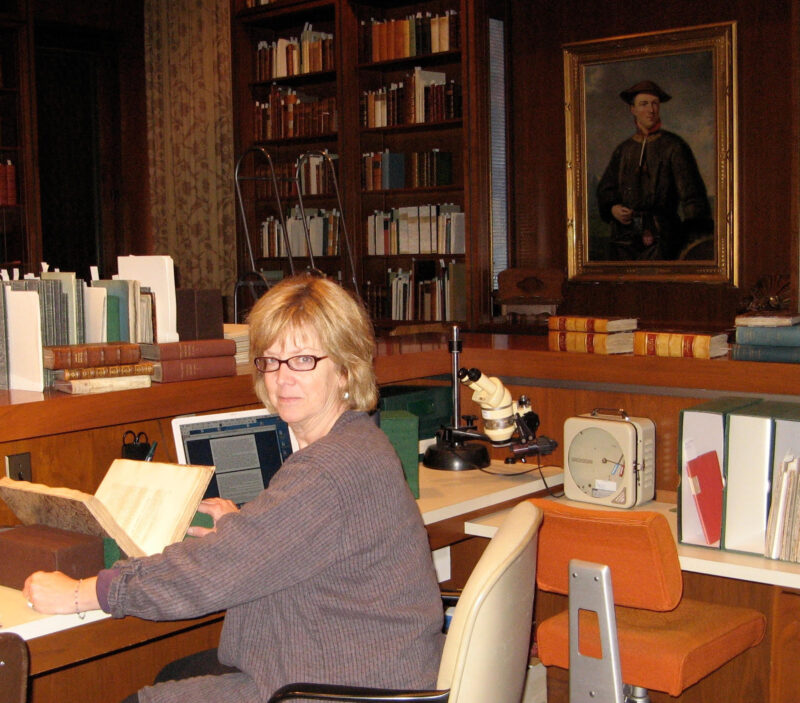

KMB: Of course. Here’s one that was a really productive tangent! I found an old clipping from a Swedish newspaper while researching in the Hunt Library for Botanical Documentation at Carnegie-Mellon University in Pittsburgh. I can’t read much Swedish, but I recognized the word häxa. Google Translate confirmed my hunch: häxa means witch. A wonderful librarian in Norway had access to a trial transcript and translated it for me. (I love librarians!) Like Linnaeus, his mother’s great-grandmother had been knowledgeable about plants and plant remedies. She brewed the best beer in town and her neighbors praised her as a “wise woman.” But when a neighbor died from a strange illness, hysterical villagers looked for someone to blame. Linnaeus’s ancestor was tortured, convicted as a witch, and burned at the stake in 1622. (I learned way too much about poor Johanne’s trial.)

ABW: Oh, that’s awful. Agreed—TMI. Way too much. Thank goodness we’ve come a long way from the era of witchcraft hysteria.

Now, tell me how long it took you to research and write this biography.

KMB: I’d say it took at least ten years, but I’ve been reading about Linnaeus for much longer—since that first walk in his garden years earlier. I find that books take as long as they need, and if you’re persistent, they’ll teach you what you need to know to write them.

ABW: Oh, I love that. Very wise.

Finally, do you have any advice for would-be biographers?

Advice for Biographers

KMB: I’d say: Don’t be afraid to follow tangents or dive down rabbit holes. Crazy as it seems, tangents can give you fresh perspectives and new angles on your subject that other people don’t see. Just make sure you can find your way back to your story! Maybe leave a trail of bread crumbs?

ABW: Bread crumbs. Perfect! What are you working on now?

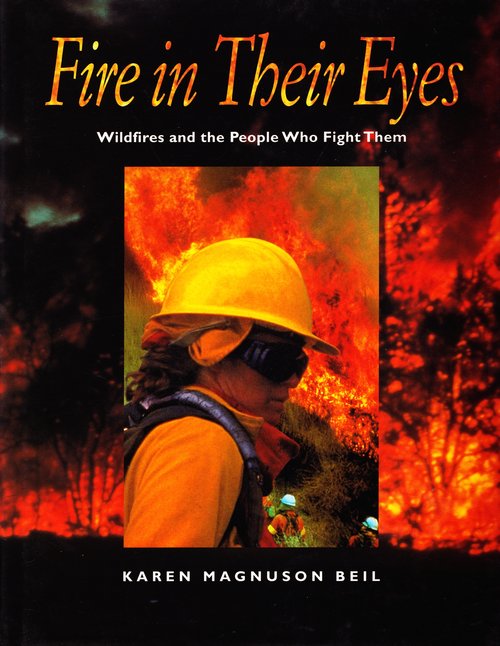

KMB: I love narrative nonfiction and I’m really interested in telling true behind-the-scenes stories about people and nature that make complex environmental issues easy to understand.

ABW: Great. I look forward to your next book. Thank you so much for doing this interview!

KMB: Thank you, Anne, for your close reading and the depth of your questions! I always enjoy your interviews. It’s fun to think and talk about our craft.

ABW: Thanks for your kind words. I could talk craft all day!

Readers: if you want to know more about Karen and her writing, visit her website here, enjoy her posts on Instagram, and check out her publisher’s website, Norton Young Readers, Norton’s Twitter feed (@NYRBooks), and Norton’s Instagram page (@NortonYoungReaders). If you do, be sure to tell me in the rafflecopter below. Each visit to one of the social media links gets you a chance to win a copy of What Linnaeus Saw. You can come back every day, entering multiple times, from now until Friday, December 11, 2020, at 11:59 PM. On Saturday, December 12, I’ll ask the app to choose a random winner. Good luck!

I recall studying Linnaeus in middle and high school. His work was fascinating even though biology wasn’t my favorite subject at the time. The book sounds like a good present for curious students!

Yes, the book would make a fun gift, especially for middle school or early high school students. Science was not my favorite subject, either, but Karen really makes Linnaeus fun. I loved her anecdotes about his inquisitive nature and how much his students enjoyed going on field trips with him. Sounds like he was quite a character.

What a lovely interview! I enjoyed learning about Karen’s writing process. I’ll have to pick up a copy of What Linnaeus Saw to share with my daughter. BTW, I’ve known Karen since I was in middle school! When I was a children’s librarian, I often read her picture books during storytime.

Anne Blankman

Anne, how fun that you and Karen know each other from way back. What a small world!

I “met” Karen through email — a friend from Vermont College connected us — but we haven’t yet met in person. Once this pandemic is behind us, I’d love to sit down with Karen for coffee. I love her writing! I wish we lived closer.

Aha! I’ve been looking forward to reading this interview for some time, and it was every bit as entertaining and enlightening as I suspected it would be. A real insider’s look at a talented writer’s process thanks to some thoughtful and fun questions. Great job!

Thank you! I loved interviewing Karen, and of course, getting her answers to my questions. I learned SO MUCH from the book and from connecting with Karen. It’s truly a joy to read wonderful books and chat with each author about their writing process!

Many thanks, Anne, and everyone for your enthusiasm for What Linnaeus Saw! It was fun to talk about a book that was, for me, such a celebration of nature. Happy reading!

Yes, truly a celebration of nature. Thank YOU for writing such a great book!