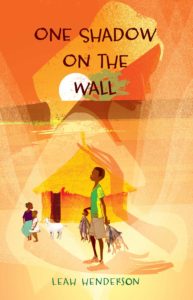

What a wonderful new book for middle grade readers! Leah Henderson’s debut novel One Shadow on the Wall took me deep into a Senegalese village and the story of Mor, a boy who desperately wants to keep his family together. Even though the setting is foreign (at least, it is for American-born-and-bred-me), the plot is the stuff of human experience: the struggle to stand up to a bully, the desire to prove oneself and make a difference, the love of family and home. It’s such a heartwarming story, I had to catch up with the author for a blog interview!

What a wonderful new book for middle grade readers! Leah Henderson’s debut novel One Shadow on the Wall took me deep into a Senegalese village and the story of Mor, a boy who desperately wants to keep his family together. Even though the setting is foreign (at least, it is for American-born-and-bred-me), the plot is the stuff of human experience: the struggle to stand up to a bully, the desire to prove oneself and make a difference, the love of family and home. It’s such a heartwarming story, I had to catch up with the author for a blog interview!

I met Leah at the 2016 SCBWI Mid-Atlantic conference in northern Virginia, ran into her again at the AWP conference in D.C. in early 2017, and attended her book launch party on June 6th in Richmond where YA author Lamar Giles hosted an insightful Q&A. Too fun!

Now I have a signed copy of One Shadow on the Wall here in my hot little hands, ready to give away to a lucky reader.

A.B. Westrick: Leah, welcome to my blog!

Leah Henderson: Thank you so much for asking me to stop by.

Goodreads Book Giveaway

One Shadow on the Wall

by Leah Henderson

Giveaway ends August 31, 2017.

See the giveaway details

at Goodreads.

ABW: I’d love for you to share a bit about your journey to write this story. Let’s start with the unique setting, Senegal. You give readers a glimpse into the people and culture of this “land of teranga (hospitality).” I especially loved the way you wove foreign words into the narrative. Jërëjëf (thank you)! In your author’s note, you talk about your travels. Please say more! When did you first journey there, and why Senegal?

LH: I have an insatiable travel bug, and before writing the novel I had been to Senegal only a couple of times. It is a place with a rich history and it had always been on my “Pack a bag” list that is miles long!

My first trip there was with my family many years ago. We were interested in visiting Gorée Island, which was integral in the slave trade, and the haunting “Door of No Return,” as well as just seeing the beauty of this fascinating country we had heard so much about. I instantly fell in love with Senegal’s spirit and looked forward to returning.

My first trip there was with my family many years ago. We were interested in visiting Gorée Island, which was integral in the slave trade, and the haunting “Door of No Return,” as well as just seeing the beauty of this fascinating country we had heard so much about. I instantly fell in love with Senegal’s spirit and looked forward to returning.

ABW: Clearly, your travels provided fabulous details that make the story come alive. One of my favorites is the “bundle of smushed plastic bags wrapped with twine.” A soccer ball. That’s just great! During your travels, were you jotting down details, or did you write descriptive passages later, basing them on photos and memories?

LH: I pretty much did all of the above. I took copious notes, never knowing what I would use and what would stay packed in cubbyholes in my mind or scattered on notebook pages. I think I filled three small notebooks on my first trip back after starting the novel. And then I had file folders on my computer filled with images of EVERYTHING I saw. I took pictures of garbage, pictures showing how dust from roadways settled on people’s feet in flip flops, and how sand clung to wet skin. Nothing in my mind was off-limits to try and capture because I did not know what might be useful later on. I believe it is better to do more research than you will ever need. Like knowing the backstory of a character—it may not all land on the final pages, but you need to know it in order to create a fully-rounded person.

ABW: Yes, it’s so true that the tiniest details matter. In this era of Google Street View, writers can “travel” all over the world via computer, but I wonder what we miss when our research is purely electronic rather than in-person. If you hadn’t visited Senegal, what details and nuances might you have missed?

LH: Google Street View couldn’t really have captured how the crinkles in a woman’s headwrap flutter when she moves, or the sticky scents of fish and sea on the air.

LH: Google Street View couldn’t really have captured how the crinkles in a woman’s headwrap flutter when she moves, or the sticky scents of fish and sea on the air.

But even more than details like those, I’ll be very honest—if I hadn’t gone back, I’m not sure I ever would’ve finished this story. Yes, people get material off the internet all the time, but for me, this particular book needed more. I had become inspired to write this story on an earlier trip to Senegal after seeing a young boy sitting on a beach wall. I really wanted to get it right for him (even though I’d only spent a few moments with him). So the pull to go back and try to figure it all out was very strong.

If I hadn’t gone back, I don’t believe I could have written a story those children truly deserve—children whose life experiences are similar to that of Mor’s (and in many ways unlike my own). I want kids like Mor and his sisters to be able to see themselves in my words and through the experiences of my characters. I want the scenes in my story to feel, smell, sound, and taste like home. I want them to see reflections of their lives on the page. And I want others unfamiliar with Senegal to be able to experience the richness of this place. I’m not sure how well I’ve accomplished this, but I know for me, it would have been a very different story had I not been fortunate enough to spend more time there while writing. I would have missed Senegal’s heartbeat through a computer screen.

ABW: I definitely felt the richness of the place! The heartbeat pulsed throughout the story. I think you really nailed it.

LH: Thank you. That means a lot. 🙂

ABW: In many scenes, Mor connects with the spirits of his deceased parents. I’d love to hear you reflect a bit about your process in weaving these spiritual threads into the story. Right from the get-go, were they part of the plot (did you set out to write a spiritually-themed novel), or did the spiritual elements emerge along the way?

LH: Family is truly important to me, and everything I write features family at its core whether it is the family you are born into or the family that grows from friendships and unique bonds. So for me the parents were always going to have strong roles. But while I was in graduate school, any time parents showed up for more than a page or two in someone’s work, everyone always said: “Get rid of them!”

LH: Family is truly important to me, and everything I write features family at its core whether it is the family you are born into or the family that grows from friendships and unique bonds. So for me the parents were always going to have strong roles. But while I was in graduate school, any time parents showed up for more than a page or two in someone’s work, everyone always said: “Get rid of them!”

ABW: Oh, right. The mantra is: “Get rid of them so the young characters will solve the story’s problem without adult help.”

LH: Yes, and that was always in the back of my head, but if I hadn’t included the parents, it wouldn’t have felt right. Although I didn’t set out to write a spiritually-themed novel, I wanted to find a way to include the parents that wouldn’t be intrusive, and that would add another layer to the story.

ABW: Clearly, you found a way to give Mor a sense of agency while weaving in some parental wisdom. Nice.

LH: I truly hope so. I loved writing the parents. They didn’t just give Mor courage—writing their scenes built up a little courage in me, too.

ABW: That makes me smile. And when I hit the paragraph with the title phrase—that was a big smile moment. I loved it! What a great title. Was it always your title, or did you (or your publisher) decide later that One Shadow on the Wall would make a great title?

LH: I love the title as well. And it has been the title since the day I wrote that paragraph (while writing the first draft). Before that there was just a placeholder that was never intended to stay. I was hoping the title wouldn’t get changed by the publisher (because we know that happens at times) and was so relieved when it didn’t!

ABW: When Lamar interviewed you at the book launch, I believe I heard you say that you spent five years writing this novel because you “wanted to get it right.” I love your perseverance!

LH: Thank you! But during those five years there was a lot of doubt about whether I was the one to tell this story, so there were long periods (months and months) where I didn’t work on it at all. At one point over half a year went by with me dragging my feet. Mor’s experience was so far removed from my own that I hesitated each time I put a word down on the page. I really didn’t want to do harm with my words, writing about an experience so unlike my own. I was focused on how I used to feel as a child—on how disappointed I was when I encountered a character that supposedly looked like me but wasn’t like me at all. It was a stereotypical representation, or just plan wrong. I did not want to be the cause of that kind of hurt for a child reading my book. I was so worried that I was going to mess EVERYTHING up, that I was stuck many, many times within those five years.

Thankfully, I had an incredible amount of support and was truly blessed to have so many people willing to answer questions and check things over for me when I stalled or stumbled.

ABW: What’s an example of something in the story that you changed because you had it wrong in an earlier version?

LH: Oh gosh, I was so nervous about putting so many words down in this story that I pretty much asked someone’s opinion at every turn.

ABW: Better safe than sorry.

LH: Yes, but of course I still tripped up at times. The largest mistake is probably the most innocent one. After having many different readers, I asked a student from Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar to read it, and he noticed something that all my other readers had failed to see or comment on. He said I had named a mangy dog after a Senegalese prophet. Not being from that culture, this fact had completely escaped me. I simply thought it was a tough name for a dog. But if I’d kept that name in the book, some readers would have gotten stuck on it, and I wouldn’t have blamed them. So, of course the dog got a new, culturally-acceptable name.

When delving into history or exploring another culture, we owe it to our readers to try our best to get things right, especially when it might be their first encounter with a certain place, or culture.

ABW: We do owe another culture our very best effort. I think the people of Senegal will thank you for this story. And I want to thank you, too, for sharing a bit about your process in writing One Shadow on the Wall!

LH: Thank you again for having me.

ABW: Readers who want to learn more can find Leah on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and at her website. There’s so much to love in this story that I could go on and on, but I’ll just end with this: read the book!

Great interview! I appreciate the care you put into your book, Leah. That’s why I loved this question, Anne: “If you hadn’t visited Senegal, what details and nuances might you have missed?” I’m glad you were able to visit Senegal, Leah!

When Leah answered my question, right away I heard the crinkle of a woman’s headwrap. I smelled fish at a salty dock. I was there. Sure, I can “walk” the streets of Dakar via Google, and the online visuals are great, but the hearing, smelling, tasting, and touching are lost. Novelists need all five senses.

Thank you for the interview, Leah and Anne. I used to host a world music radio program, and Senegalese musicians were well represented: Youssou N’Dour, Ismael Lo, and Baaba Maal. I was hoping to take a trip back when my son was in elementary school and his school had partnered with schools in Mali, Mauritania, and Senegal, but I couldn’t take off work for that long. The principal, the school librarian, and another parent went, and I got to hear their presentations.

Lyn – It seems like every time I hear from you, I learn about another one of your many interesting experiences. It’s amazing how much you’ve done and how extensively you’ve traveled. Editing the MultiCultural Review for all those years was a great fit for you. It’s no wonder that you now do translations as well as writing your own fiction. I look forward to your next book!

L. Marie and Lyn, thank you so much for taking time out to read our interview.

Senegal is a place near and dear to me and I am so glad I had the opportunity to go back and truly experience it–eyes & heart wide open. And Lyn, the first time I heard Youssou N’Dour perform I was living in Italy and I remember thinking everything about those moments while he sang with his voice echoing around the piazza–that was perfection. It was what perfection was. 🙂

Jërëjëf, ladies!

Now I need to listen to the music of Youssou N’Dour! Thank you, all.