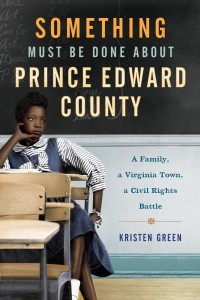

If you read only one book this summer, make it Something Must Be Done about Prince Edward County. Part memoir, part journalistic exposé, this sensitive and compelling book explores the history of a Southern town where local history wasn’t taught even though a suit filed on behalf of black students in the county was one of the five consolidated into Brown vs. Board of Education. Author Kristen Green alternates between memories of growing up there, enjoying time with her family’s black housekeeper, extensive research and interviews, and dreams for her own children, who are multi-racial.

If you read only one book this summer, make it Something Must Be Done about Prince Edward County. Part memoir, part journalistic exposé, this sensitive and compelling book explores the history of a Southern town where local history wasn’t taught even though a suit filed on behalf of black students in the county was one of the five consolidated into Brown vs. Board of Education. Author Kristen Green alternates between memories of growing up there, enjoying time with her family’s black housekeeper, extensive research and interviews, and dreams for her own children, who are multi-racial.

I couldn’t put it down.

It struck me that in terms of craft, journalists can teach novelists a lot. So I caught up with Kristen (she lives in Richmond, VA—lucky me!) to get her insights into writing about tough topics.

A.B. Westrick: Kristen, welcome! And thank you for doing this blog interview. Your book has so many layers—such complexity distilled down to about 300 pages—that we can’t do it justice here. But we sure can talk craft…

You tell us how University of Mary Washington professor Steve Watkins (who happens to be a novelist now, just sayin’) helped you hone your journalistic grit. After you got “worked over” by a “nice” administrator, “‘The hell with nice!’ Watkins snapped. ‘Nice doesn’t mean good!’” (pg. 90). In another anecdote, you tell us that your former history teacher shut down your interview with the message “loud and clear: She’s done talking about this, and she thinks [you] should stop, too” (pg. 198).

So let’s discuss the born-to-be-nice problem. How do you handle tough moments like that? When an interview gets uncomfortable, what do you do?

Kristen Green: I think it’s like writing. Don’t give up too quickly. It’s tempting, when things start getting interesting, to pack up and say you’ve got enough information. But that is the time to push a little bit harder. I’ve been a journalist for a long time and confrontation is just part of who I am. I do not shy away from conflict.

I tend to keep asking questions, to follow a natural succession, to want to go deeper with each question. People expect writers to ask the hard questions, so my advice is just go for it. Assume that whomever you’re interviewing wants to talk about the tough stuff or is at least expecting you to ask about it. If you do it respectfully, and if you’re patient, you can get really good information you never expected to get. But don’t be in a hurry. And keep going back to the person over and over to ask follow up questions. New information will be revealed. One really great trick is to just be quiet at various points in the interview. Leave some space for the person you’re interviewing to fill—sometimes the interviewee will be so uncomfortable that they just talk to avoid silence.

I tend to keep asking questions, to follow a natural succession, to want to go deeper with each question. People expect writers to ask the hard questions, so my advice is just go for it. Assume that whomever you’re interviewing wants to talk about the tough stuff or is at least expecting you to ask about it. If you do it respectfully, and if you’re patient, you can get really good information you never expected to get. But don’t be in a hurry. And keep going back to the person over and over to ask follow up questions. New information will be revealed. One really great trick is to just be quiet at various points in the interview. Leave some space for the person you’re interviewing to fill—sometimes the interviewee will be so uncomfortable that they just talk to avoid silence.

ABW: Oh, yes—those uncomfortable silences. Been there. And as for going deeper and not hurrying—fiction-writers need to remember that, too. Great points.

While we’re on the topic of tough stuff, let’s talk about shame. On page 70, you recount the moment you realized your grandfather had been a key player in the decision to close the schools. Your sense of shame permeates the book, bringing authenticity to the page. Can you reflect a little bit about shame as a motivating force in writing?

KG: I think shame is what kept this book idea alive for me. When I got to college, I was ashamed to realize that I didn’t know what had happened in my hometown before I was born, and I felt like that was a story I needed to learn. As I began telling other people’s and other communities’ stories as a journalist, shame popped up again. I was confronting my white privilege. And then, when I met my future husband Jason, a multiracial man, I knew I wanted to marry him and have kids, and I was ashamed to be from a place that might reject our love—and that historically had done everything in its power to prevent white and black kids from going to school together.

When the book project became more serious and I realized my grandfather had played a bigger role in the school closures than I had imagined, the sense of shame became more pervasive. I couldn’t just blame my town—my family was at fault, too. I was wrestling with what to do about this information because I loved my grandfather desperately, and I wanted to be a loyal granddaughter. In the world I grew up in, talking about these topics—shame and privilege and oppression and intermarriage—was a big no-no. It was something swept under the rug. And I was confronting not just my own shame, but this sort of community shame that was so deeply ingrained that some people, both black and white, couldn’t access it. Confronting shame—and sitting with it—was an important part of writing this book for me.

ABW: I appreciate your honesty, and I can definitely relate to the challenge of confronting white privilege. (In 2014 I did a guest-post on racism, privilege, and shame at School Library Journal’s “Teen Librarian Toolbox.”) Before we wrap this up, I want to ask about your writing process. In your Acknowledgments, you thank your husband for “his constant faith that I could write this book, even when I lost my way…” I’d love to hear more about losing your way, and particularly how you found your way again, once you’d lost it.

KG: I didn’t know what I was doing. I was just feeling around in the dark, trying to figure out how to build a book. I had all the information I needed—and if I didn’t have it I could easily get it—but I hadn’t the foggiest idea how to stitch it all together. I knew how to interview people and how to write up those interviews in lovely little scenes. I knew how to write snippets of my own life. But doing deep historical research and then boiling down what I learned for readers, to create something that explained my hometown’s complicated history? I had no idea how to do that. And how to weave reportage and history and memoir all together into a cohesive book? I didn’t have the first clue. There were many days, weeks even, when I was consumed by self-doubt, and it felt like I would never be able to pull a book out of the disparate material I had amassed.

I have always worked in a newsroom with layers upon layers of managers. This was the first time in my writing life where no one else had the final say about a piece I wrote. I would have to remind myself daily that no one else could solve my writing problems. It was up to me. And sometimes that pressure was too heavy.

But I just kept showing up. I took my husband and close friend’s advice and got up at 5:00 a.m. to write before I looked at email or social media or dealt with my kids. I kept trying different ways to structure the book, mapping it out on notecards on my dining room table. I sought feedback from my editor and from writers I trusted and admired. When I got really frustrated, I took a break or did another book task. I made sure to read at night, so that good writing—and the structure of really great books—would sink into my brain. But mostly I just showed up each day and wrote the pieces that, when combined with other pieces, would come together to create a book.

ABW: Just showing up at the page—so true. I’ve learned a lot here, not only from your answers, but from reading Something Must Be Done about Prince Edward County. Long after turning the final page, I’m still thinking about your book. Thank you again for a great interview, Kristen, and for writing such a heartfelt book.

What a great interview! I’ve heard of this book. So glad you interviewed Kristen!

Yes, this book is getting lots of press — and it’s well deserved. Oprah Magazine mentioned it. NY Times Sunday book review, etc. — her website lists all the recognitions. And I’m just super lucky to live where Kristen does! For two years, I’ve known that she was working on it, and it was fun to get my own signed copy at her release party. I expected the book to be good, but it was better than good. Blew me away. Great book. Just great.