Every time I read a masterfully written novel, I sit back in awe of the author’s craft. Then I re-read to glean tips and techniques for my own writing. When I’m lucky, the author says “yes!” to an interview, and today, lucky me, lucky us—look who’s here to talk craft! The award-winning, New York Times bestselling Sara Pennypacker, author of Pax, the Clementine books, the Waylon series, and many more.

Before we get to the interview, I have giveaway details, of course! Hop to the end of this post to enter the drawing to win a copy of Sara’s 2020 release, Here in the Real World, published by Balzer+Bray. Then come back to hear about Sara’s process in crafting this compelling, funny, and brilliantly plotted book. The deadline to enter the giveaway is Tuesday, February 16, 2021, at 11:59 PM.

A. B. Westrick: Sara, welcome to my blog.

Sara Pennypacker: Thanks for inviting me!

ABW: So let’s talk about Here in the Real World! It’s full of characters who pulled my heart-strings, and I want to start with them, or actually, with their nicknames. (They cracked me up.) Grandma is “Big Deal” and the protagonist’s mom is “Little Deal,” and what I love is that you don’t explain these names. They’re simply part of the fabric of eleven year-old Ware’s life. So my question is about their origins. In your own family, are nicknames a thing? When you write, how much time do you spend deciding on names for characters?

SP: No, we aren’t a nickname family—it was strictly a writing trick. The right name (or, especially, the right nickname) does a lot of heavy lifting for the writer invisibly. Without a written descriptor about Ware’s mother or grandmother, or the relationship between them, the reader knows a great deal about who Big Deal and Little Deal are. I usually have to write quite a bit of the book and get to know the characters for a good long while before their names come to me. Clementine was the record hold-out—I actually sold the book without her being named—the manuscript just had an X wherever she was addressed.

ABW: Oh, no way. Too funny. That’s great.

Now, we have to talk craft—I’m always in search of writing advice. Some of my awe in reading your fiction comes from the way themes emerge organically through the story. In Here in the Real World, the up-front theme is about fairness and a knight’s code of honor, but there are also many subtle themes, such as Ware wishing his parents would see him as “terrific just the way he is,” and the notion that “everything was something else before and will be something else after.”

My question is about your process. When you first begin writing, do you know what your themes will be, or do they emerge along the way? I guess I’m really asking how much of this novel fell into place during revision, and how much was already in your mind at the get-go?

SP: That’s such a good question, and such a hard one to answer. In fact, theme is evasive at first in every book I write. Most of the time, it goes something like this: I think I know the theme of a book as I’m beginning it, but halfway through the theme I was trying for shows itself as heavy-handed or forced, or just plain unimportant to the characters or story.

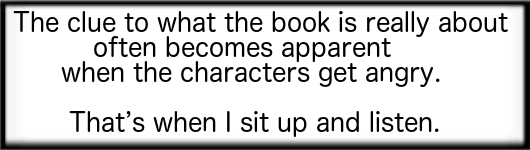

The clue to what the book is really about often becomes apparent when the characters get angry. That’s when I sit up and listen. Then I go through the manuscript and find the places it was hiding all along and I start layering it in elsewhere.

ABW: Oh. Anger. That’s really interesting.

SP: I hate the word message, and I truly understand it’s not my job to lecture to kids. But in Here in the Real World, I do have something to say to kids—just an encouragement and a shout-out. It’s this: one thing that has always struck me when I interact with kids and we’re talking about real problems in the real word—the effects of war on kids and animals in Pax, for instance—the kids always move me by how eager they are to do something. “What can we do?” “How can we make it better?” they ask. I love that so much.

So in Here in the Real World, I show three different kids using three different methods to address the problems that concern them. And the adults in the story model how to handle problems well, too. As Ware’s mother says, “Look around the edges. There’s always something you can do.”

ABW: Yes, there’s always something! I especially loved the part where your character Ashley seeks to DO SOMETHING—to help the cranes, after learning that birds sometimes break their legs when they mistake asphalt for water in the dark. The poor things! Where did you hear about this? Did you set out to reveal this fact (and other environmental issues) in the story, or was your starting point something else?

SP: Many years ago, I heard a poet read a poem about her experience of coming upon a hundred geese who had broken their legs trying to land on an icy road, pre-dawn in Wisconsin. That poem was devastating. It has haunted me, or the images have, and since hearing it I always knew that I would pass the experience on in some literary way.

Creation is a river that way—you probably have had it happen also—an artist will experience something, then create a work of art that expresses it, and another artist will be moved by that piece of art and process it through her own medium, and so on and so on. The truest human experiences are constant across time and space, and are always being revisited through different lenses. Each artist translates her experience into her own language so it might affect others (just as I have Ware’s uncle explain it in the story).

Anyway, no, I didn’t set out to write about it, but when my character Ashley needed some kind of environmental injustice to care about, there it was.

ABW: Sara, that is so rich. Yes, yes, yes! And oh, my, those poor geese.

Now, tell me what your process is like, when you set out to write something. When you’re beginning a new book—when there’s a blank page in front of you—what gets you started?

SP: Oh, I never have a blank page in front of me! At least not a blank first page.

ABW: Hahaha. That’s awesome.

SP: So far at least, by the time I am at the end of one book—the slogging-through-the-weeds-on-every-word-choice stage before turning in the final draft—I am chomping at the bit to begin the next. And I feel lucky that it’s always been a choice. I have too many ideas, not too few. However, most of them are really BAD ideas! Luckily though, at this stage of my writing life, I have developed reliable rules about what projects I will take on, which are right for me, and which will have broad appeal.

My own personal three criteria: first, that it’s an idea I have not been able to let go of for at least a month; next, that at the heart of it is some form of injustice that I can right in story form; and finally that if the character I’m envisioning were beside me on a street corner, I’d jump out in front of a careening bus to save her/him.

ABW: Oh, that’s a good image. And the belief that you can right something in story form—I love that.

SP: Thank you. Once I’ve met all three conditions, I feel confident that I’ll have the energy and passion to see the project through. A novel is a tough beast to tame, so a writer has to really love it.

ABW: Yes, a tough beast, and time-consuming. You’ve written lots of books for young readers. Over the years, has the process of writing gotten any easier? What advice do you have for aspiring authors?

SP: No, it’s never gotten easier. And I hope it never does! It sometimes feels that for every book, I must learn to write all over again. In every single book there has come a point at which I suddenly realize there is a problem I cannot solve. I am dramatically forlorn—the book is no good now, it was a stupid idea, and I will have to admit to my agent and editor that I’m unskilled and worse, a fraud…blah, blah, blah. Every single book.

And every time, the answer comes from the best piece of writing advice I’ve ever heard: “THE STORY IS THE BOSS!” from Stephen King’s On Writing. I go deep to find out what this specific book wants to be and how I am supposed to serve it, and I learn whatever it is I need to learn and then I sit with that problem until I break it.

What has changed is that after 25 books, I’ve come to expect this stage, to laugh at it and even welcome it. I know how hard it must be for new or aspiring authors to hit blocks and not have the literary history to give them confidence, so I hope it’s at least cheering to know that an old-time like me still goes shaky every time.

ABW: I love picturing you laughing at yourself and even welcoming the problem you can’t solve. Pushing forward and going deep—this is great advice.

Last question: what are you working on now?

SP: I’m well into a new novel and I’m having a blast—it’s a blatantly allegorical comedy with very sharp edges. Almost a year ago, when we were just learning what an enormous problem this pandemic was going to be and how incredibly, inexplicably, criminally, inadequate and dangerous Trump’s response was, I was getting so worked up I thought I might actually have a heart attack. But then I began hearing an indignant voice in my head, channeling all my outrage about people who value money and power above all else, and telling me a story about one extraordinary little girl named Leeva…

ABW: Ooooohhh… I can’t wait to read it! And meanwhile, I see that your sequel to Pax is coming out this year—Pax, Journey Home—and I want to read that one, too.

Thank you so much, Sara, for doing this interview!

SP: I enjoyed it. Thanks for caring about those geese.

ABW: I’m haunted now, picturing the geese. But it’s good to be haunted in this way.

Readers, if you want to know more about Sara and her writing, visit her website here, and check out her posts on Facebook and Twitter. If you do, be sure to tell me in the rafflecopter below. Each visit to one of the social media links gets you a chance to win a copy of Here in the Real Word. You can come back every day, entering multiple times, from now until Tuesday, February 16, 2021, at 11:59 PM. On Wednesday, February 17, I’ll ask the app to choose a random winner. Good luck!

Interesting interview – the writer is prolific and enjoying it. Enjoyed reading about her process.

Thank you, Lenore, for reading my interviews every month without fail! When Sara mentioned how a character’s anger helps her appreciate what a story is about, I saw my own work-in-progress in a new way. Good stuff!

What a great interview! I sooooo love this quote: “The clue to what the book is really about often becomes apparent when the characters get angry.” Makes the theme seem a lot more natural.

I love that line, too! After Sara said it, I pulled up a chair beside one of my characters and had a good sit-down-and-listen.

Anne, your interviews are always thoughtful, always a conversation I’m eager to listen in on, thank you! Sara’s three criteria make me ask myself what my criteria are for knowing an idea is “the one” to tackle next. What is the singular passion that drives each of my books? For Sara, one is an injustice she can right with story, such a great one. I love how this makes me think.

Yes! Sara’s comments made me think, too. And thank you for your kind remarks about my interviews. I love diving into craft!

Thank you for this insightful interview, Anne and Sara! In one of my forthcoming books, I didn’t know what my theme was until a brilliant member of my critique group (Patrick Downes, for all you VCFA’ers) pointed it out. I couldn’t decide if the book was YA or adult and he said, “You may think it’s about the teens’ struggle for freedom, but it’s really about leaving home.” I was about seven chapters into the book at the time and no one had actually left home but he was right.

What an insightful comment from Patrick. Leaving home. That theme could resonate through a story on so many levels. I’m with you, Lyn, that when I’m writing, rarely do I know what my themes are. I’m always pushing myself to get closer to the characters — to get under their skin — and sometimes themes run even deeper than skin. They’re subconscious.

What an enjoyable interview. I tried to find the poem about the geese but was unsuccessful. Any chance Sara mentioned the name or author of the poem? Thanks!

Sara didn’t mention the name or author of the poem, but I was so moved by the image, I looked for the poem, too. I believe I found it, but it’s been a year, and I just saw your comment today, and at the moment I can’t put my finger on it! I’ll look again. Back in touch soon…

I’ve heard back from Sara that the poet’s name is Shana Deets, but we haven’t been able to locate the poem, itself.