Oops, I did it again.

No, no, I haven’t broken a guy’s heart à la Britney Spears, but I’ve repeated the same mistake that earned me a decade-worth of rejection letters: writing from my head. Allowing my scenes to drift into the safe world of ideas. Into thoughts and concepts and heady stuff, and out of the dangerous world of feelings and sensory responses. I need to stop pretending that I have my act together and instead revisit the times I’ve felt vulnerable, insecure, embarrassed, and scared.

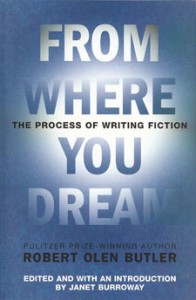

This month I’m re-reading Robert Olen Butler’s From Where You Dream in order to shake myself up, wake up my writing, and dig deeper into each moment. I’ve challenged myself to craft a novel in alternating points-of-view (four characters), and it’s coming along, but lemme tell you… thinking is easy. Feeling is hard. People often ask writers where they get their ideas, and for me this question misses the mark. Ask me how I tap into emotions. (I’ll tell you I’m working on it.) Butler says:

This month I’m re-reading Robert Olen Butler’s From Where You Dream in order to shake myself up, wake up my writing, and dig deeper into each moment. I’ve challenged myself to craft a novel in alternating points-of-view (four characters), and it’s coming along, but lemme tell you… thinking is easy. Feeling is hard. People often ask writers where they get their ideas, and for me this question misses the mark. Ask me how I tap into emotions. (I’ll tell you I’m working on it.) Butler says:

… in order to get through childhood and puberty and adolescence and young adulthood, broken relationships and a marriage or two, or four—you have identified with your mind… you’ve got this self-conscious metavoice going all the time… That voice wants to drag you up into your head… [but] the only way to create a work of literary art is to stop that voice. Your total attention needs to be on the sensual flow of experience from the unconscious.

You’ll need to read the book to grasp everything he’s saying, but for now let’s call it digging deeply for the unconscious physical responses that accompany the emotions we feel. Digging really, really deeply. An author who has mastered the ability Butler talks about is Patrick Ness. Right now I’m reading Ness’s latest novel More than This, and I want to show you the opening sequence so you can see the way he’s crafted a “sensual flow of experience.” Check this out:

In these last moments, it’s not the water that’s finally done for him; it’s the cold. It has bled all the energy from his body and contracted his muscles into a painful uselessness, no matter how much he fights to keep himself about the surface. He is strong, and young, nearly seventeen, but the wintry waves keep coming, each one seemingly larger than the last. They spin him round, topple him over, force him deeper down and down. Even when he can catch his breath in the few terrified seconds he manages to push his face into the air, he is shaking so badly he can barely get half a lungful before he’s under again. It isn’t enough, grows less each time, and he feels a terrible yearning in his chest as he aches, fruitlessly, for more.

He is in full panic now…

Wow. These paragraphs draw me into the present moment of the story. I don’t know how the character ended up in the water—and it will be many chapters before Ness supplies the backstory—but already, I care about this character. I’m beside him in the water, and I’ll keep reading to find out what happens.

Years ago I read Butler’s book and it helped me understand “show, don’t tell” (I blogged about details), but this time I’m digging deeper than details. I’m going into places that feel dangerous, places where my characters feel vulnerable, places that are a whole lot harder than details to tap into.

All of this is to say that I’ve developed coping mechanisms to avoid emotional black holes, but these same mechanisms—the ones that keep me sane—block my fiction. They block a reader’s ability to connect with my characters on an emotional (subconscious) level. I need to let myself feel scared again, or angry, or embarrassed, or humiliated. Really feel it. Then I must write scenes without using words like scared, angry, embarrassed, or humiliated. I must write the sensory details of the experience.

(An aside: my sister is a nutritionist and dietician who specializes in eating disorders, and just last week was telling me that she’ll sometimes ask her clients to sit still—just sit for as long as they can, for an hour even, or two hours—and allow themselves to feel. To experience their own emotions. It can be a terrifying exercise, but she promises them they won’t die in the process. They might cry, tremble, rage, etc., but they’ll survive. The technique has helped some of her clients, and it got me thinking (oooh, here I am, thinking again): I need to tap into the place where I tremble.)

I’m guilty not only of writing from my head, but of repeating this mistake even though I’m aware of it. How about you? What are your mistakes? What is your comfort zone—your default button—the place you retreat to, where you pat yourself on the back for having penned another scene that sounds oh, so good when the truth is that it’s nowhere near honest? Not yet.

What an insightful post, Anne! I’m judging YA fiction for the Cybils this year, and the book I read last night wasn’t working for me but I couldn’t identify who. After reading your piece, I realized the author had done the same thing–writing a perfectly-structured story in alternating POV from her head, but lacking emotional power and resonance. The plot twists were clever, but I didn’t feel as if I was there, with the characters. Yes, books “from the head” do get published, especially if they’re cleverly plotted, but they could be so much more.

Oh, and the mistake I commit over and over? Falling back on cliches of language, characterizations, and scenes rather than finding a distinctive way of presenting my story.

That’s great that you’re one of the Cybils judges this year!

I know what you mean about clever plot twists lacking emotional power. When I’ve tried to craft neat plots, my stories have fallen flat. I need to get inside my characters and let them drive the plot, and never impose a plot upon them.

Kudos to you for identifying a mistake you tend to make. I say — let the cliches rip during the early drafting stage, but when it’s time to polish, be ruthless in cutting them! Since you know that’s your weakness, you’ll be on the lookout for them. All good.