Bringing History to Life: a writing workshop

You can adapt this lesson plan for use with any historical setting, and turn it into a dynamic collaborative workshop (language arts concepts/social studies issues). I focused on Reconstruction (the setting for Brotherhood) and based the structure on the work of Carol Kuhlthau, et al, in Guided Inquiry Design: A Framework for Inquiry in Your School. This workshop encourages students to engage with primary source documents and enter into the period: smell it, touch it, hear it, feel it!

You can adapt this lesson plan for use with any historical setting, and turn it into a dynamic collaborative workshop (language arts concepts/social studies issues). I focused on Reconstruction (the setting for Brotherhood) and based the structure on the work of Carol Kuhlthau, et al, in Guided Inquiry Design: A Framework for Inquiry in Your School. This workshop encourages students to engage with primary source documents and enter into the period: smell it, touch it, hear it, feel it!

You will need:

- photographs (provided),

- newspaper articles (provided),

- a map of the place you’re discussing in class (here you’ll find a map of Richmond, VA, after the Civil War),

- sound files (provided), and

- writing supplies (paper & pencil, or computer/word processor).

Participants will glean insights into:

- What it might have felt like to live in Virginia shortly after the Civil War.

- How imagination can bring to life any historical time period.

- How our five senses draw us into a scene.

- How messy the writing process is (and how fun it can be)!

If time permits, ask students to research the period of Reconstruction and identify interesting photos and newspaper articles. If time is short, use the photos and articles I’ve found. (I guarantee that if given enough time, your students will discover the same primary source documents that I did.) In this PDF you’ll find a set of Reconstruction-era photos, a post-war map of Richmond, VA, and source citations.

To begin the writing component, ask students to take note of the details in the photographs. For example, here is a section of a photo taken in front of St. John’s Church in Richmond, VA. Notice that the children are wearing coats, but their feet are bare.

Other details to note include the horses and carriages, cobbled streets, the motley garb worn by klansmen at that time, and hatch marks on the map, indicating the large section of downtown Richmond that burned in the April 1865 fire.

Here’s a worksheet students may use to jot down details. Click on the image for a printable PDF:

Once students have tuned into the details of the time period, ask them to imagine that they live in Virginia after the war and that they might be one of the people in the photographs, or that they encounter these people when they walk the streets.

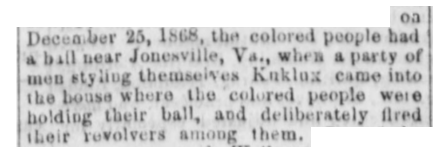

Next, distribute the newspaper articles found in this PDF. (All of these articles refer to the KKK. If you’d prefer not to ask students to write about the Klan, use this PDF set of articles.) Each student will need one article. Here is a section of one of the articles, published in the Bristol News on March 19, 1869:

Beneath each article, you’ll see one or two writing prompts. I usually ask students to begin with the words BAD WRITING at the top of their page/computer screen, giving them permission to make messy first-drafts, loosen up, get creative, enter into the moment, and let the writing flow without worrying about spelling or grammar. Later, they can clean up/polish their writing. (This is how many professional writers (including yours truly) work. A blank screen or piece of paper is a terrifying thing, but once you scribble a few words, you’re onto something.)

Ask students to write the scene described in the newspaper article, beginning, “I was there. I saw it happen…” Encourage them to write quickly (whatever comes to mind) and

- add physical description like colors and sounds.

- What are the textures of things around them?

- What is the weather?

- What does the air smell like?

- What are people saying?

- What emotions do they feel?

After they’ve written for a few minutes, play a sound file and ask them to incorporate the sound into their scene. Here are 3 sound files to choose from (click on each image to listen):

Church Bells:

Horses:

Crickets:

Once students have created a messy first draft, ask them to exchange newspaper articles with a friend and repeat the exercise with a new/different article. Play a different sound file during the second go-round. Write quickly!

After students have completed two drafts describing different moments, ask which one they liked more, and why? What made one more compelling than the other? What else might you want to know about what happened? Later, you might encourage students to polish the scene they preferred. (They’ll always prefer one over another, and the act of choosing one helps students take ownership of the activity.)

Follow-up discussion may take different forms, depending on grade level, and on the class (language arts or social studies).

Here are suggested questions for discussion afterward:

- Imagine you’re holding the original newspaper and the ink from that paper has stained your fingertips. Rub your fingers together. What does the ink smell like? What do your fingers smell like?

- Who do you think might have written the article you’re holding? A man? A woman? What might the race of the writer have been? How might the writer’s gender and race have influenced what s/he chose to write?

- If you had written this article, what might you have changed? What would you have deleted? If you were to re-write it, what details would you include?

- What questions do you have about what’s going on in the article? What do you want to know more about?

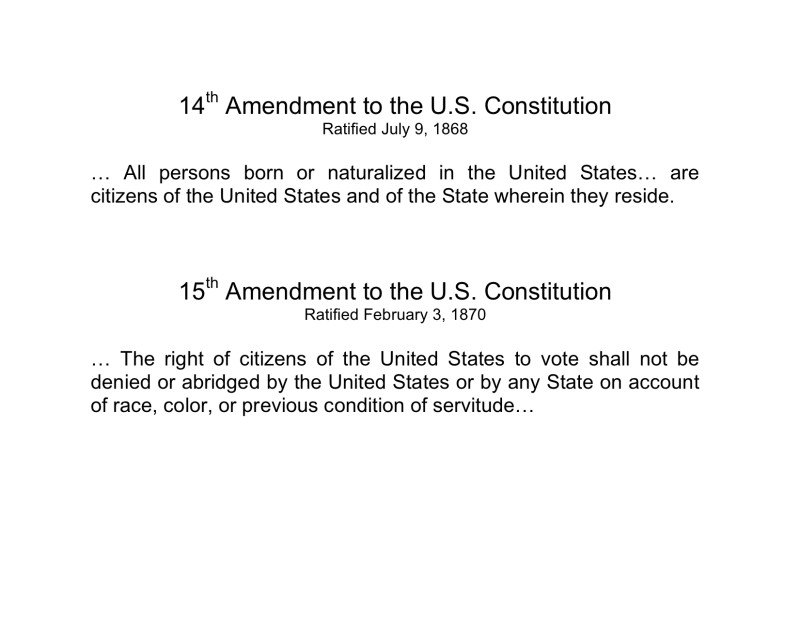

Follow-up in social studies class might also include a discussion of the 14th and 15th amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

Once students have responded to the writing prompts and imagined what it might have felt like to live during Reconstruction, they’ll better understand the need for these amendments. Questions for further discussion might include:

- The 14th amendment grants citizenship to all people born in the United States, and the 15th grants voting rights. What role might these amendments have had in spurring some people to join organizations like the KKK?

- Write a scene in which you’re walking to your polling place on Election Day in 1871 and someone wearing a “ghost costume” confronts you. Describe the moment in detail. What do you do?

- If you lived during Reconstruction and you were an African-American man, would you have voted? Why or why not?

- [Elementary Level:] What would you think if every 4th grader got two votes for every one vote that a 5th grader got?

- What do you—today—right now—think of the 15th amendment? Do you personally know any adults who don’t vote on election day?

- Imagine that you’re 18 right now and you can vote. Who might feel threatened by your right to vote?

- In what countries around the world do some people today feel threatened by others’ rights?

- What might it be like to live today in the United States and not be a citizen?

Follow-up in language arts class might include analysis of a number of literary techniques. The story in Brotherhood lends itself to discussion, for example, of topics such as point of view, voice, protagonists versus antagonists, dialogue, opening in media res, endings, emotional arcs, and plot structure.

In addition, you might ask students to polish those messy first-drafts. Here are a few of the techniques that I use when it’s time to polish my writing:

- Identify adjectives and adverbs and (wherever possible) replace them with strong nouns and verbs. Delete unnecessary words.

- Replace feeling-words (happy, sad, angry, etc.) with actions, letting readers infer the emotion from the description of what the character does.

- Adjust the length of sentences and the tense of verbs. Short, choppy sentences in the present tense create a sense of urgency while longer sentences in the past tense allow readers to relax and reflect.

- Read the writing out loud. Sometimes I’ll ask someone else to read my writing to me. I listen for what works and what doesn’t, then revise.

If time permits, conclude this lesson by inviting students to share their stories in a creative way. Along the way, ask them to reflect on this workshop, itself. The Guided Inquiry Design encourages reflection as a way of helping students see themselves as learners and appreciate that they are learning how to learn. Consider guiding them to inquire:

- What surprised me today?

- What did today’s work make me think of?

- What was clear? What was confusing?

- What do I wonder about?

- Where do I want to go from here?

I hope this collaborative lesson helps teachers and students improve their writing while imagining what it might have felt like to live in the American South during Reconstruction. If you try this workshop in your school, please email me at abwestrick (at) gmail (dot) com and let me know how it went. I’d love your suggestions for ways to improve this lesson.

I’d also love to visit your school and guide students through the workshop! To arrange for an author visit, please email me at ABWestrick (at) gmail (dot) com.